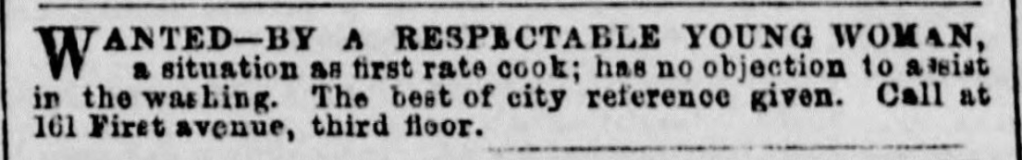

Women in the nineteenth century apparently did everything they could to avoid doing laundry. Some people—especially city dwellers—sent their washing out for others to do. Families who could afford it employed domestic servants for such things. Even some servants looking for employment preferred to work as cooks and chambermaids rather than as laundresses. Why was the job of washing clothes and household linens so distasteful? How, exactly, was this onerous chore done? And was it really that hard to produce linens that were “white as snow”?

The basic requirements for a household laundry were a plentiful water source; a fireplace or stove for boiling water and heating irons; good ventilation; wide, sturdy benches for holding laundry tubs when in use; at least one sink with a drain for emptying out the dirty water; and suitable indoor and outdoor drying areas. For houses without a separate laundry room, the kitchen was used for washing and ironing. Period sources emphasize the importance of soft water for good results; consequently, lye, potash, or soda ash (sodium carbonate or washing soda) was added to hard water to soften it. Rainwater was preferred because it is naturally soft.

Laundresses needed a variety of supplies. Catharine E. Beecher provides a handy list in A Treatise on Domestic Economy for the Use of Young Ladies at Home and at School (1841). “Two washforms [benches] are needful,” she says—one to hold two tubs for the suds, “and the other for the bluing water and starch tub[s].” In addition, she advises having “four tubs, of different sizes; two or three pails; a large wooden dipper; a grooved wash-board; a clothes-line (sea-grass, or horse-hair, is best); a long wash-stick to move the clothes in boiling; and a wooden fork to take them out.” Other necessities included soap dishes, an indigo bag, a bottle of ox gall to preserve colors, starch, clothespins, and a brass or copper kettle for boiling clothes (iron was to be avoided as rust would create stains). Additionally, Eliza Leslie recommends having a lye barrel, a barrel for soft soap, and clothes horses (The House-Book, or A Manual of Domestic Economy, 1840). Ironing required even more equipment.

Soap was produced at home with lye, a strong cleansing agent that was made by adding boiling soft water to wood ashes, preferably hickory or oak. For making soap, lye was combined with animal fat (beef or pork was best); lime; and, for hard soap, salt. Women also used “washing soda” (sodium carbonate) to launder white cotton and linen fabrics. “A very great improvement in economy of labor has become common, namely, soda washing,” Catharine Beecher wrote in 1841. “Much prejudice has been excited against the method because, if it is not done with proper care, it injures the texture of the cloth.” She advises diluting it with soap. Later in the century, commercially made laundry soap became widely available. In any case, these harsh detergents wreaked havoc on women’s hands.

Monday was traditionally laundry day (ironing was done later in the week). But this was the subject of some debate. Eliza Leslie suggested that Tuesday was better so that items could be sorted, soaked, and mended on Monday, leaving Sunday free. Mrs. Henry Ward Beecher (née Eunice Bullard) disagreed with those who wanted to “break up the custom” of washing on Monday. In order to preserve the Sabbath, she advised soaking the laundry on Saturday night. Why change things if “good and sensible housekeepers” had been satisfied with Monday for so long?, she asks in “Why Is Monday Recognized as the Washing-Day?” (Christian Union, January 10, 1877). In Motherly Talks with Young House-Keepers (1873), Mrs. Beecher exclaims: “If it were not for the washing, housekeeping would lose half its terror. But I rise every Monday morning in a troubled and unhappy state of mind, for it is washing-day! The breakfast will surely be a failure, coffee muddy, meat or hash uncooked or burnt to a coal, everything untidy on the table, and the servants on the verge of rebellion.”

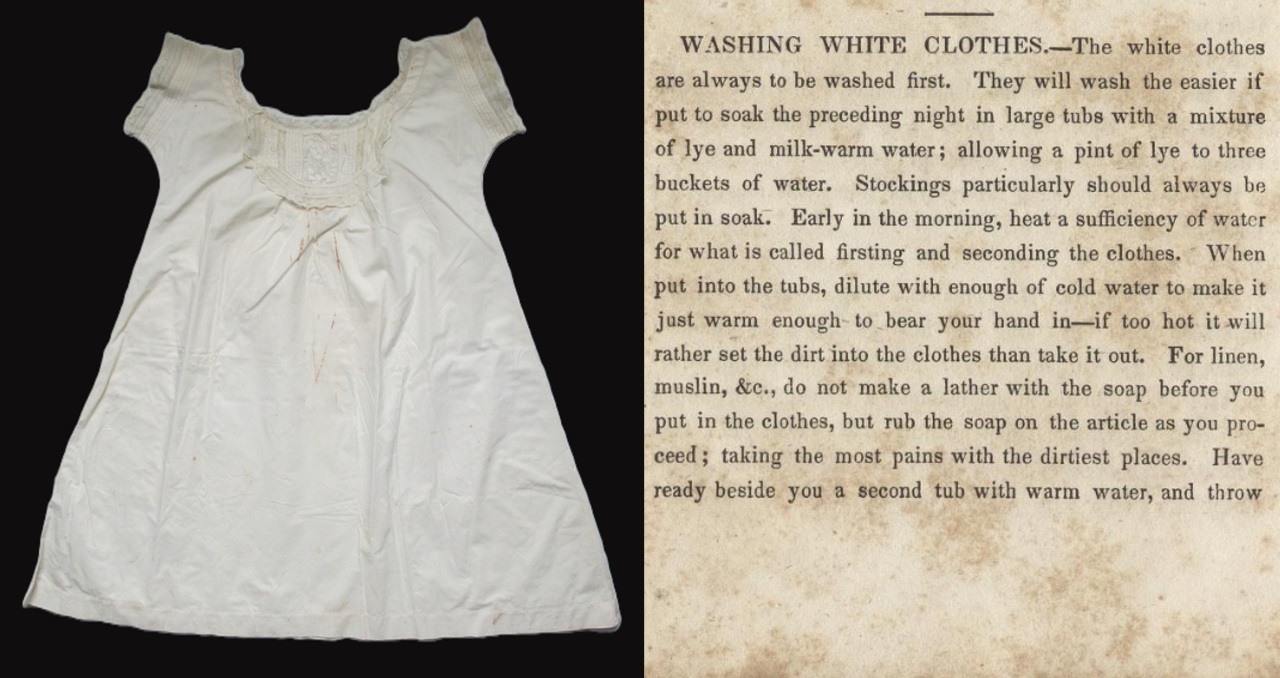

The washing process was cumbersome. First, the dirty laundry was sorted, with separate groupings for colors, whites, flannels, and fine items. Then, the whites were soaked overnight. On washing day, the laundry was boiled, washed, wrung out, scrubbed, and rinsed multiple times (although this process varied somewhat depending on individual methods and the item being laundered). After washing, white items were rinsed in water tinged with a small amount of blue dye. Bluing was preferably made of indigo, but a compound of Prussian blue pigment and starch was also used. Because white fabric yellows over time, blue offsets this change in color and results in renewed snowy-white perfection. Starching was next, a process that period sources often describe in detail, including how to make and use various starches. Catharine Beecher’s simple method, however, was to dip things to be stiffened in starch just before hanging them out to dry. Whites were ideally dried outside in the sun; colors, wrong side out, were hung in the shade. Everything on the clothes lines had to be taken indoors before sunset. “If still not dry, spread them out on the wooden clothes-horses or hang them on lines in a garret, back kitchen, or in any convenient room, if you have not a laundry,” Eliza Leslie counsels. In bad weather, the wash had to be dried in a warm room, either in the laundry or in a special room set aside for this purpose.

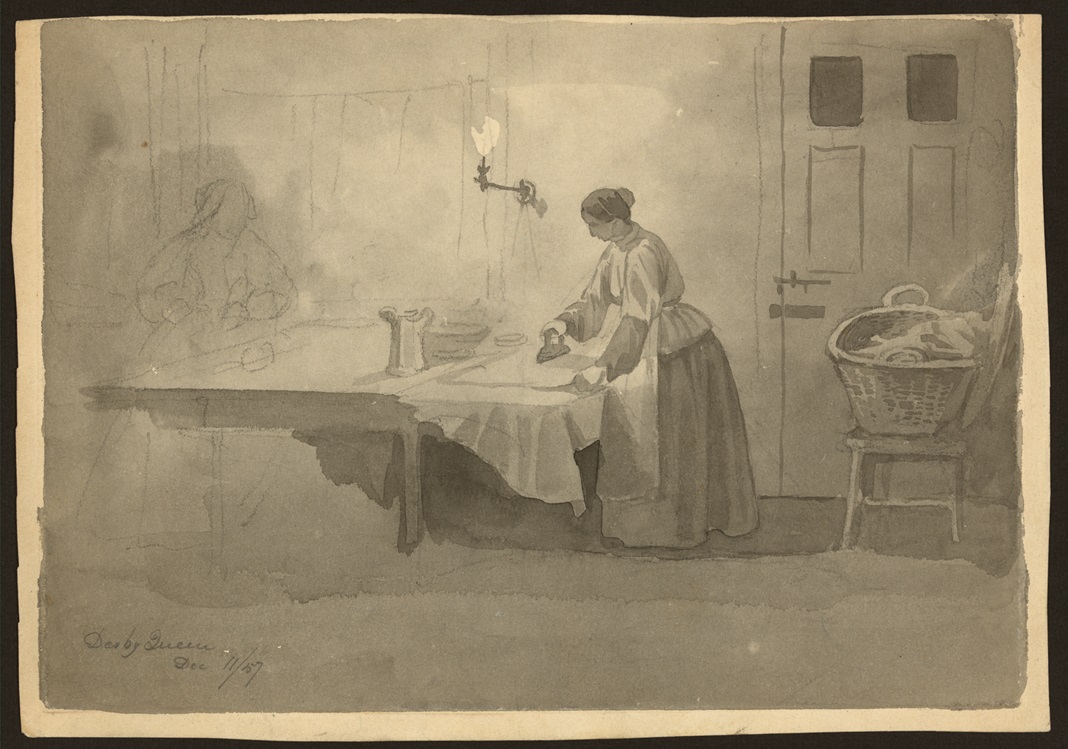

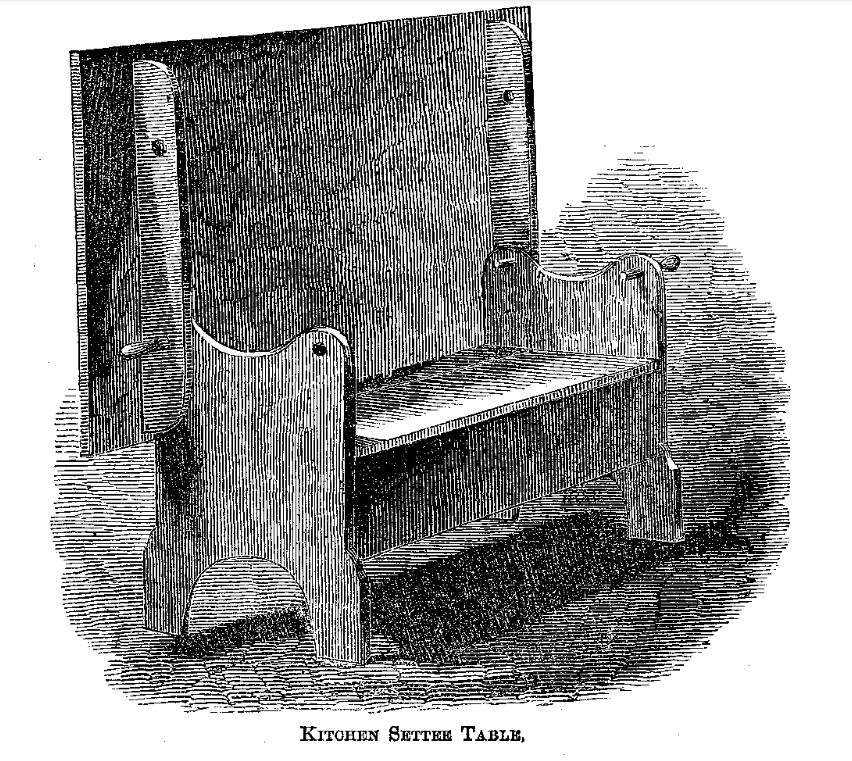

Ironing was usually done on a large table. But there were other options. Eliza Leslie describes a collapsible ironing board connected to the kitchen wall with hinges. Some households had a kitchen settle, which was a wooden settee with a high back that could be lowered to create an ironing table. The work surface was covered with a large, thick, woolen blanket topped by a smooth linen or cotton sheet pinned at each corner. Although there were several kinds of irons (known as “smoothing irons”), the most common was the flat iron, which ranged in size from four to ten inches. Specialized ironing accessories, such as a “skirt board;” a “bosom board” for pressing gentlemen’s shirts; and a fluting iron for ruffles, made these tasks easier. Eliza Leslie specifies that every person engaged in ironing should have at least three irons at their disposal. When the iron became too cool, a hot one was ready to take its place. “For ironing, have a clean well-swept hearth and a large, clear, broad fire with plenty of bright hot coals,” she counsels, “as they heat the irons much better than a blaze.” (And some housekeepers heated their irons on a stove.) In addition, Catharine Beecher says to have “a piece of sheet-iron in front of the fire on which to set the irons” and an “iron-stand” placed on a piece of wood to prevent the “very hot irons” from scorching the ironing surface. Clothing and linens were sprinkled with cold water before ironing, and beeswax was rubbed on the hot irons to ensure smoothness. Some households had a mangle—a weighted press with rollers—for table and bed linen. In Eliza Leslie’s opinion, “mangling machines” were well worth the expense because they achieved superior results while “saving the time and trouble of ironing these articles.”

In 1860, a thirty-five-year-old Irish immigrant named Bridget Connor worked as a laundress near New York City at the elegant country estate of Robert and Maria Bartow. Bridget—unlike the Bartows’ Irish-born cook, chambermaid, and coachman—was illiterate, which may have contributed to her settling for a position that many domestic servants did not want. As was common practice, one or more of the other servants probably helped her as needed. After all, there were fourteen people in the household in 1860—eight family members and six servants. (By comparison, the Bartows’ neighbor Philip Schuyler had eighteen people living in his house, including an illiterate Irish-born laundress and an English seamstress.) The sheer volume of undergarments, petticoats, nightclothes, stockings, shirts, sheets, tablecloths, napkins, towels, and clothing to be washed, starched, dried, ironed, and folded must have been a challenge.

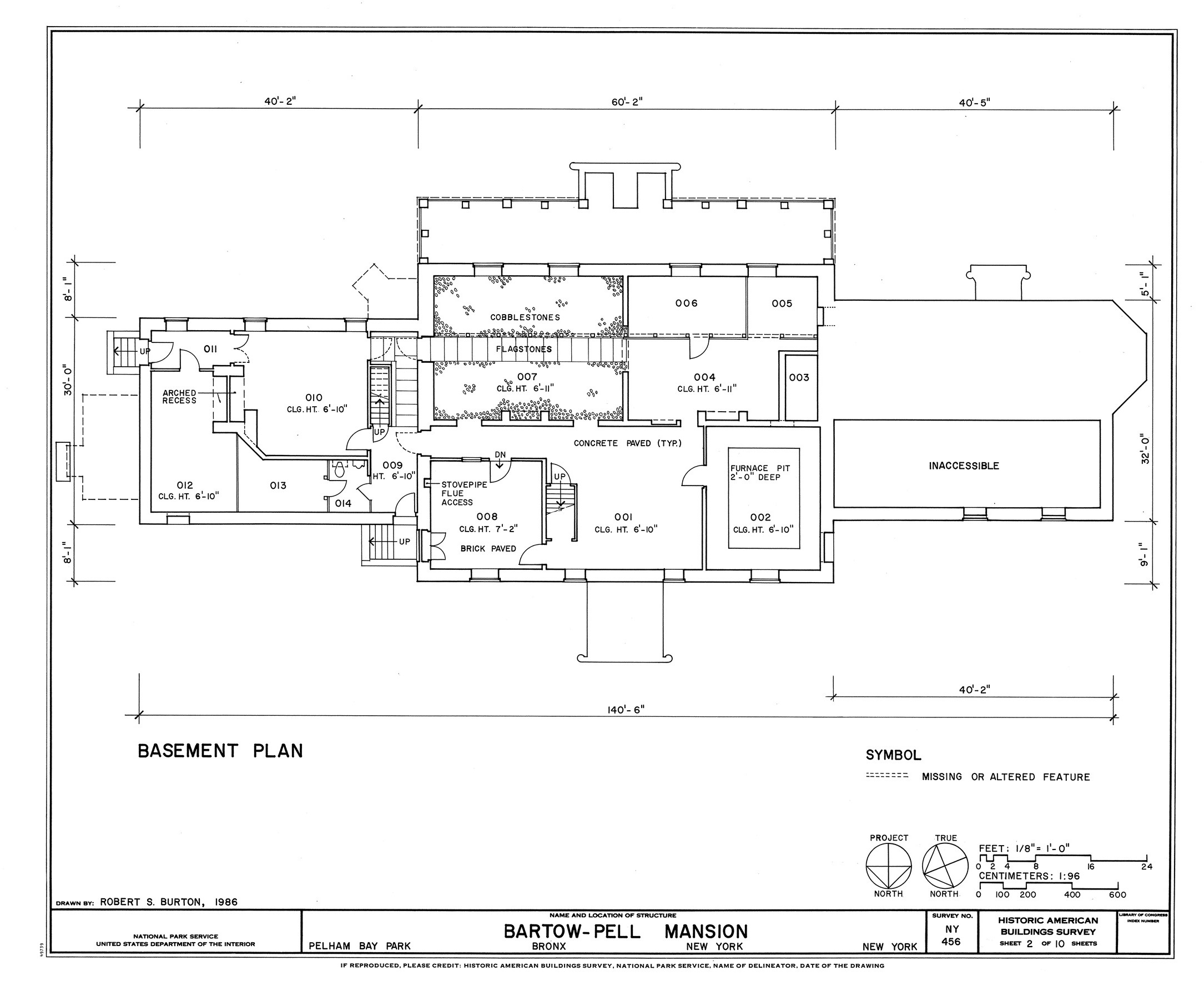

The Bartow mansion was built between 1836 and 1842, and we can get a good idea of their laundry room from Eliza Leslie, who wrote in 1840: “No large house should be without a laundry . . . It should have a large fire-place for the convenience of boiling several kettles of water at a time, if necessary, and for heating the irons. A pump or hydrant should either be within the laundry or close to the door; also a sink for disposing of the dirty water.” We do not know where the Bartows’ laundry was located, but physical evidence in the unrestored basement and mid-nineteenth-century textual sources help us to theorize about where it might have been.

In Bartow-Pell’s Historic Structure Report (1987), Daniel Hopping and Zachary Studenroth conclude that the historic kitchen was originally on the first floor, possibly because “a relatively high water table rendered the basement unfit for such a function.” Nonetheless, the authors found that “the basement spaces preserve significant historic details,” and although they do not speculate on how these areas were used (other than for storage), it is impossible to ignore several clues that point to the laundry being situated in the rooms beneath the double parlors. This large space includes a cistern, two fireplaces, good ventilation, and an intriguing floor treatment.

We do not know how rainwater in Bartow-Pell’s brick-walled and plastered cistern was collected or distributed, but Hopping and Studenroth found “an inlet . . . in the west foundation which may have provided a source of water” for it. In any case, the following description explains how these systems worked: “A large cistern should be dug, paved and walled with brick and coated with water lime . . Tin or wooden troughs should be fastened along the eaves to conduct the water to the cistern. A small cast iron pump . . . should be placed over the kitchen sink and should be supplied with water by a leaden pipe from the cistern.” (“The Kitchen and Its Accessories,” The Ohio Cultivator, May 15, 1853) Two fireplaces in the mansion’s basement correspond to those in the parlors above. “For a laundry, a large fire-place is better than a stove,” Mrs. Leslie cautioned, “as the latter will make the room intolerably hot in the summer.” Four original tri-part windows line the exterior-facing walls in this area of the basement. “It is essential that a draught or current of air should be excited in a drying-room, or a laundry used as such, to carry off the moisture from the linen. This current may be obtained by keeping a part of the upper sashes open, or [having] panes to open.” (Thomas Webster and Mrs. Parkes, Encyclopaedia of Domestic Economy, New York, 1855) Finally, the floor in the largest room is made of cobblestones and divided lengthwise by a flagstone path. This floor is original, according to Hopping and Studenroth. Cobbles were traditionally used on roads for drainage but are occasionally seen in basements, such as in the Samuel Stearns house in Northfield, Massachusetts (1819–24). Bartow-Pell’s cobbled floor is located on the side of the house facing Long Island Sound, where good drainage would have been essential to control flooding. Would this feature also have been helpful in a laundry room?

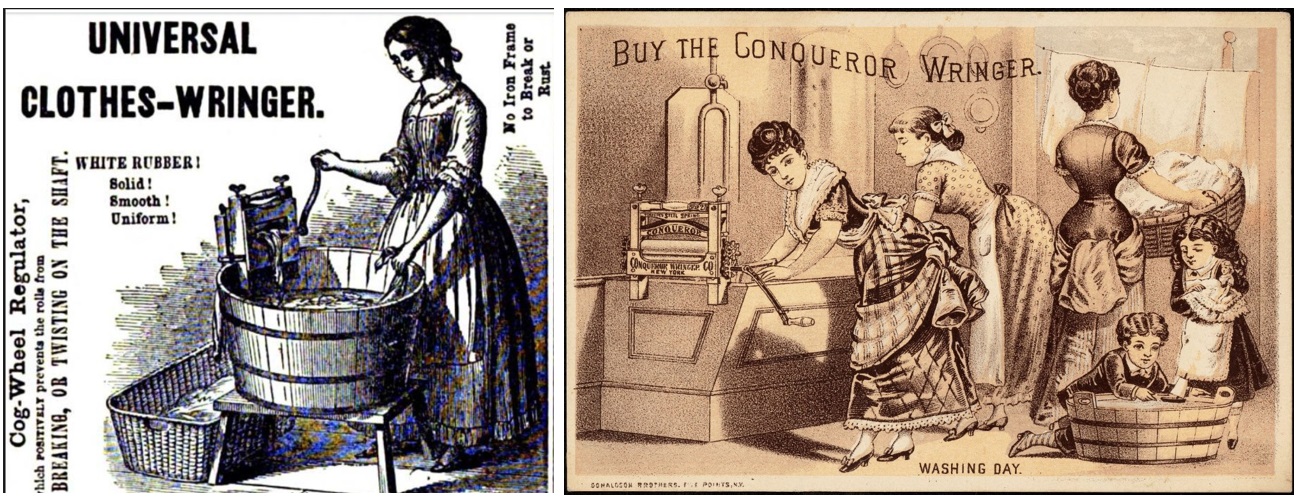

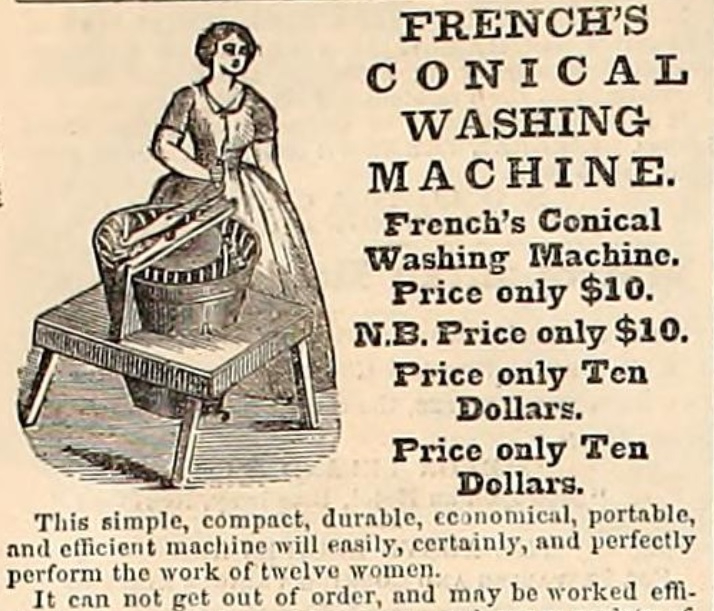

During the second half of the nineteenth century, technology improved. More houses had indoor plumbing. Laundry sinks (“stationary wash tubs”) were common. Better equipment and even washing machines made work easier. New machinery, however, did not seem to make laundress jobs more appealing to young women looking for work. In 1882, the matron of a Children’s Aid Society facility in New York City complained about the “difficulty of finding girls willing” to be trained in this field. “Most of them avoid laundry work as they might poison,” she bemoans. (Documents of the State of New York, 1882) Things would not really change until well into the twentieth century, but, luckily, the extreme dread of laundry day is now part of history.

Margaret Adams Highland, Bartow-Pell Historian

I’ll be saying my thanks to modernizati