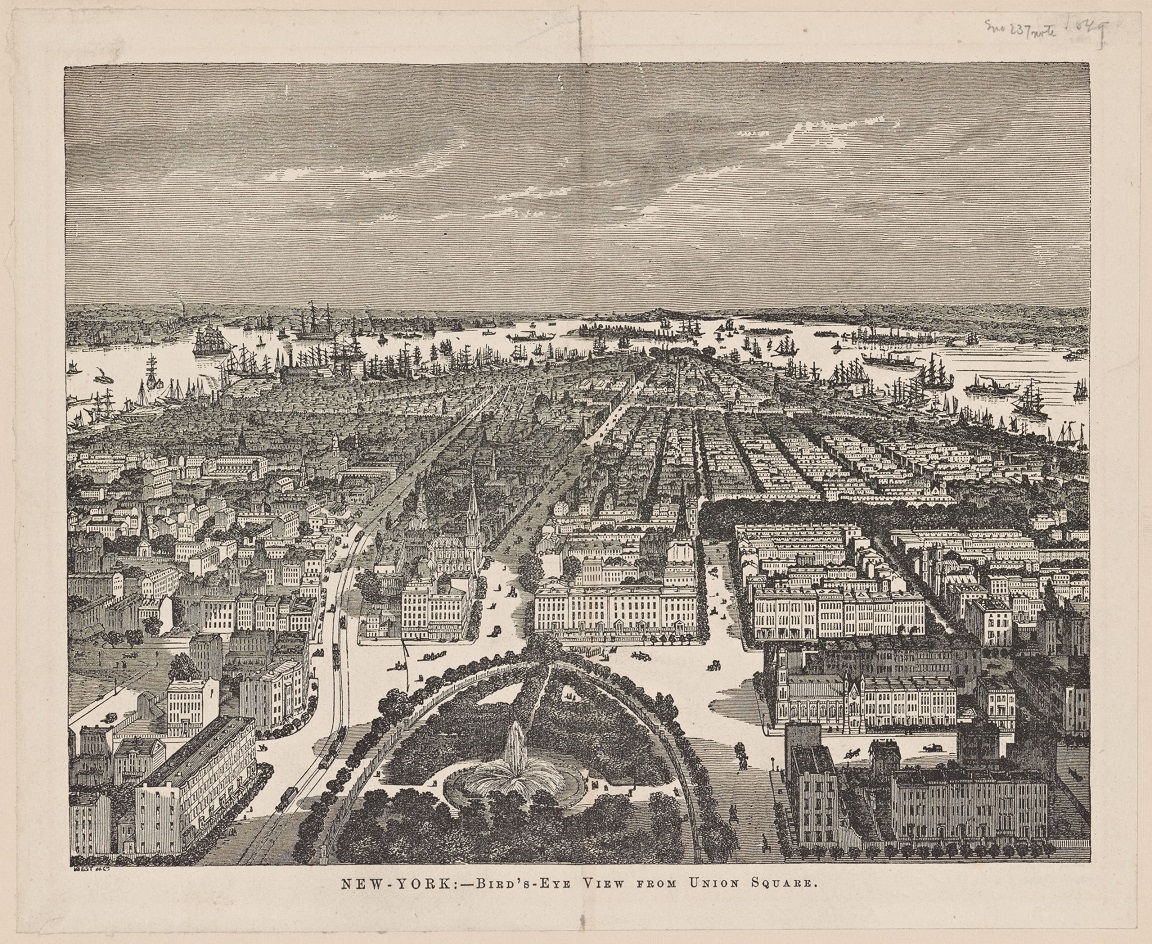

Where did stylish people shop in antebellum New York? Broadway, of course. But selecting a new bonnet or visiting one’s tailor were not the only reasons that locals and tourists alike were drawn to the most exciting street in the metropolis. The great thoroughfare was also THE place to see and be seen. Sumptuous hotels—such as the Astor House—and landmarks including Trinity Church, St. Paul’s Chapel, Barnum’s American Museum, Niblo’s Garden (the famous pleasure garden and theater), and City Hall added to the vibrant scene.

This view from about 1846 faces south down Broadway. P. T. Barnum’s American Museum (left) opened in 1841. St. Paul’s Chapel can be seen across the street with the recently completed spire of Trinity Church in the distance. Astor House—a now-demolished luxury hotel that was completed in 1836—is the large porticoed building at the right across from City Hall Park.

The handsome ballroom of the Astor House provides a sophisticated backdrop for the season’s latest evening fashions (top), while stylish dandies promenade on Broadway across the street (bottom).

Broadway began as a Native American trail, became a road under the Dutch, and continued to evolve as an important street in the British colonial period. What would eventually become the city’s longest thoroughfare kept growing as commerce continually pushed residential blocks farther and farther uptown.

“Broadway, the most splendid street of the city, runs N. from the Battery, about 3 miles, with a breadth of 80 feet,” the Gazetteer of the State of New York explained in 1836. “It is the great and fashionable resort of every thing which inhabits the city, and at some hours of the day, in fine weather, is inconveniently crowded with carriages and pedestrians.” Ladies peered out of fine carriages while young men dashed about in sporty tilburies and phaetons or trotted by on horseback. In the meantime, heavily laden carts and wagons carried deliveries, and packed horse-drawn omnibuses transported masses of men and women to and from work. “From six to seven, Broadway roars—nay, thunders with the noise of omnibuses bearing their freight of the morning back to their residences up town,” J. H. Ingraham tells us in “Glimpses at Gotham” (The Ladies’ Companion, February 1839). Meanwhile, glittering shop windows tempted shoppers and flaneurs with everything from silks to cigars. At night, after gaslights were installed on Broadway, the street was brightly illuminated. “As twilight approaches, the city is suddenly lighted up with its million of gas flambeaux, and inflammable air ignited into brilliant flame succeeds the light of the sun,” Ingraham wrote admiringly.

This view shows Broadway as it appeared in 1849 from the steeple of St. Paul’s Chapel and includes Barnum’s American Museum, Genin’s Hatters, and Mathew Brady’s daguerreotype studio. The spire of Trinity Church, which had recently been rebuilt by Richard Upjohn and was the highest structure in the city until 1890, rises prominently in the distance. Pedestrians stroll the busy sidewalks, and carts, carriages, and a large number of omnibuses fill the street.

“Broadway is the fashionable lounge for all the black and white belles and beaux of the city,” the British memoirist Mrs. John Felton observed in Life in America (1838). Mrs. Fenton’s account is only one of numerous sources describing the racial mix on Broadway. In “Glimpses of Gotham,” we learn that “between ten and eleven at night seems to be their [the Black population’s] fashionable hour for promenading.” And in 1842 Charles Dickens wrote about “Negro coachmen and white” in American Notes.

Did people of fashion favor one side of Broadway? Absolutely. The west side of the street was what it was all about. “At this hour [around five o’clock in the afternoon], everybody walks not to shop or on business, but to see and be seen. The whole of the Western side-walk then reminds one of a promenade in a ball-room—two currents being constantly moving in opposite directions . . . doing nothing in the world but look and stare at one another.” (“Glimpses at Gotham”) The thrill of mingling with the haut monde even prompted Ellen Sutphen, a domestic servant, to don her employer’s expensive clothes “and promenade the fashionable side of Broadway as large as life,” the New York Herald reported on May 18, 1859. “On missing Ellen from her accustomed place in the kitchen, [her mistress] sent a policeman after her and had her arrested. On being taken to the station house, it was found that silks and satins to the amount of $160 graced the fair form of the frail prisoner.” The west side was known as the “dollar side.” This was “from the fact, I suppose, that all the fancy stores are upon that side” of Broadway, William M. Bobo concludes in Glimpses of New-York City by a South Carolinian (1852). The east side, on the other hand, was called the “shilling side.”

In 1848, Ball, Black & Co, a prestigious retailer of jewelry, silver, and fancy goods, moved into a new shop with elegantly appointed showrooms at 247 Broadway across from City Hall.

Crossing the street, however, was no easy task. In fact, it was downright dangerous, and accidents were common. “A few days ago I was occupied in the third story of [Mathew] Brady’s [photography] establishment on the corner store of Fulton and Broadway,” William Bobo recalled, “and I noticed two young ladies who wished to cross over to the ‘Dollar Side’ . . . of Broadway. They made repeated attempts, but failed. . . . After a while, one made an effectual trial, but . . . they were separated; this was too bad. They remained in this predicament for nearly an hour, when ‘a jam’ occurred between a ‘bus and a dray, which stopped the current, and the girls got together.” Newspapers of the period often include reports of pedestrians suffering grave injuries. “Yesterday morning a lady residing in Bleecker street, while crossing Broadway, was run over and seriously wounded by the horse treading on her foot. Great blame must be attached to the driver of the cart.” (Morning Herald, July 2, 1838)

This scene from the 1850s depicts heavy sleigh traffic on Broadway in front of Barnum’s Museum.

Broadway was simply too congested. Although it was touted as spanning a spacious eighty feet, nineteenth-century sources reveal that this measurement included the sidewalks, which left only forty-two feet for the actual carriageway. In 1851, Joel H. Ross counted 1,200 vehicles in one hour passing by the spot where he stood. “The gong-like, tornado-like, oceanic, unceasing roar and tumult of this bustling street make it less inviting than it otherwise would be to promenaders who love to chat, as well as walk,” he observed in What I Saw in New York. Finding a solution to relieve this overcrowding proved difficult, despite a number of plans that were proposed over the years to fix the problem. Disruptions from a seemingly endless building spree did not help matters. “Broadway is like a boy who grows so fast that he can’t stop to tie up his shoes,” Joel Ross whined. “Doors, windows, walls, roofs, brick, stone, mortar, dust and splinters daily come tumbling down to make way for banks, stores, halls, hotels, shops, offices, &c. &c.”

In this print from 1836, shoppers and strollers along Broadway share the sidewalks with merchandise displays, dogs, and wooden barrels, while omnibuses, stylish carriages, horses, a wagon delivering ice, and more dogs crowd the street.

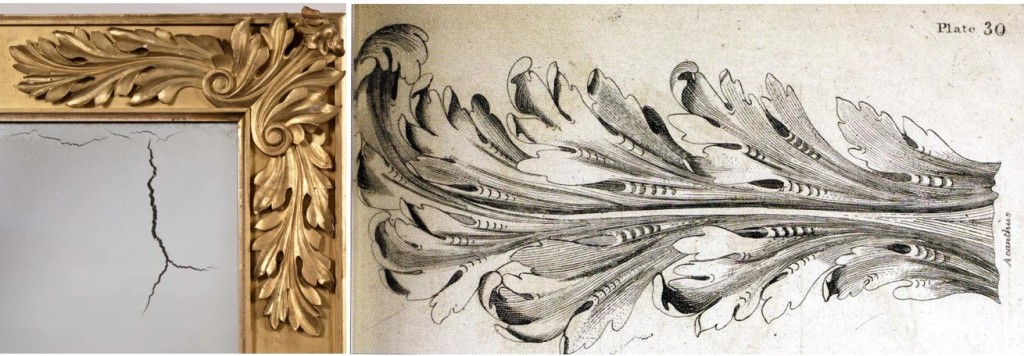

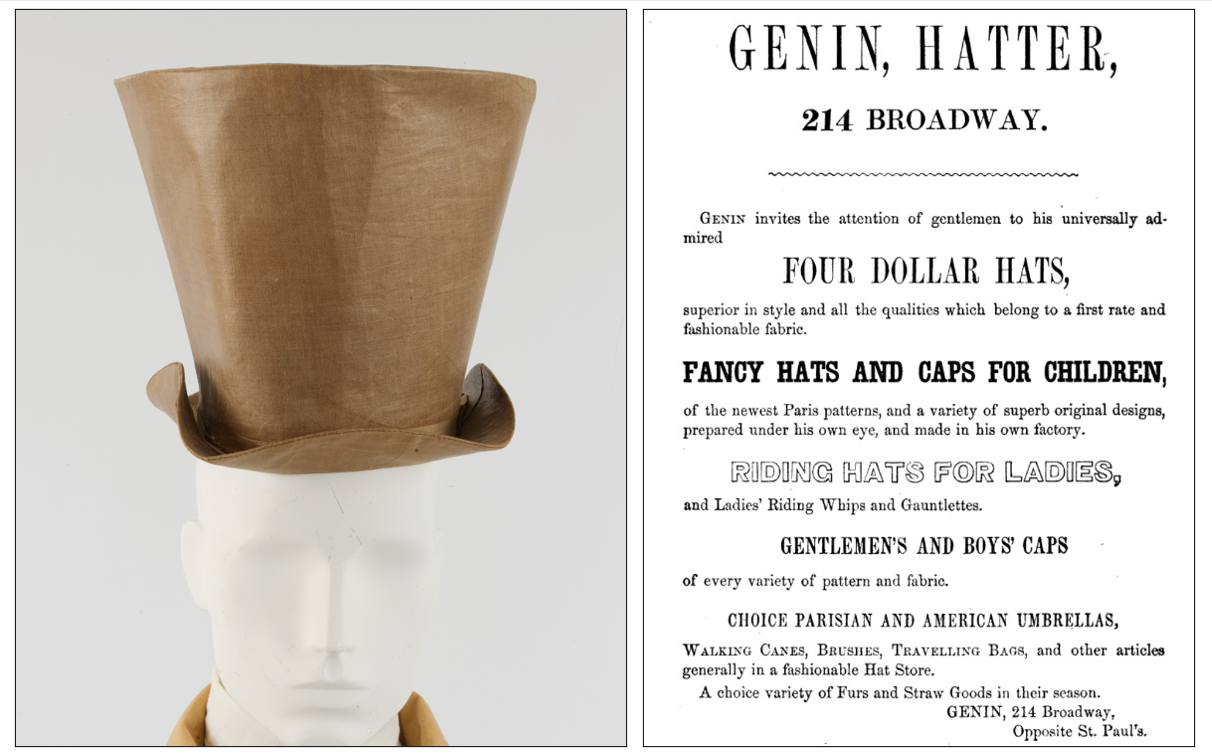

John N. Genin (1819–1878) operated his well-known hat shop at 214 Broadway—next to Barnum’s American Museum—where he sold hats and caps, walking canes, umbrellas, traveling bags, and furs. In 1850, when P. T. Barnum launched Jenny Lind’s American tour in New York, his neighbor Genin, “the celebrated Broadway hatter,” recognized an opportunity for some publicity (as did many other merchants) and gave the superstar Swedish singer a black beaver riding hat bedecked with velvet and satin ribbon, rosettes, and a black plume. “The Jenny Lind Riding Hat” “was worn by the fair lady in her morning rides,” Godey’s Lady’s Book announced in December 1850. In 1853, Genin was among the Broadway shop owners who participated in the Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations at New York’s Crystal Palace.

In March 1842, the New-York Visitor and Lady’s Album, sang the praises of shopping on “Broadway—dear Broadway!” “Between Cedar and Canal Streets, shops, tastefully adorned, meet the eye on either hand. Here are displayed, in their most alluring dress, the wares of booksellers and music venders—dealers in silks, satins, and laces—importers of toys, carpeting, and annuals—confectioners and perfumers—merchant tailors, hatters, and jewelers: in short, every article which can please the fancy.”

Perhaps you stopped at Tiffany, Young & Ellis (later Tiffany & Co.) to pick up a new pair of opera glasses or select a special piece of jewelry for your spouse. This “splendid fancy-store” offered “agreeable and fanciful trifles, from the rose-wood dressing-case to the pearl headpin; fancy boxes for odorous [i.e., sweetly scented] gloves and handkerchiefs; [and] silver and gold fillagree articles of every variety.” Their large inventory also included “Chinese fabrics and productions of all kinds, excepting opium, which is prohibited” (just to be clear!). (The New Mirror, December 30, 1843) If you were looking for a new piece of music to learn for your pianoforte, or even a musical instrument, you could take a look at Hewitt & Co. on the corner of Broadway and Park Place. Were you in the market for a new carpet, oil cloth, or drugget (a woolen cloth laid over a carpet to protect it)? Just head to Peterson & Humphrey at 379 Broadway on the corner of White Street. “In the great carpet-house of Peterson & Humphrey are offered the productions of the best looms in the world, in a variety and profusion probably unequalled elsewhere in America. The principal saloon is like a street, and it is almost always thronged with people.” (“The Palaces of Trade,” International Monthly Magazine of Literature, Science, and Arts, April 1852) And if you needed a pick-me-up in the midst of all this shopping, Thompson & Son confectioners provided elegance and comfort “for ladies and gentlemen who visit the city but for a part of a day, . . . to lunch or dine, or for those who come down Broadway to do shopping and need a resting place, or enjoy an exchange for gossip.” In 1852, the popular confectioner moved into a brand-new building at 359 Broadway, which James Thompson had commissioned from the architectural firm of Field & Correja at great expense. (Mathew Brady’s studio was subsequently located on the upper floors.)

A shopping trip to Broadway was not complete without a visit to one of the famous dry goods emporiums (the precursors to department stores). The grandest of them all was owned by Alexander T. Stewart (1803–1876), an Irish Protestant immigrant whose merchandising savvy made him one of the wealthiest men in the United States, with a fortune that rivaled that of William B. Astor. In 1846, Stewart moved into a new and larger store a block north of City Hall—his famous “Marble Palace,” a five-story showplace in the latest Italianate style made of Tuckahoe marble, which dazzled shoppers with its rotunda and imported French plate-glass windows. Henry James recalled visiting the store as a child, “the ladies’ great shop, vast, marmorean, plate-glassy and notoriously fatal to the female nerve,” he wrote in A Small Boy and Others. After dark, a multitude of gaslights lit up the building. Stewart broke with precedent when he built this magnificent edifice on the unfashionable shilling side of Broadway. “Stewart’s is the only retail dry-goods store on the east side of Broadway; . . . but the scarcity of stores will compel some of the great establishments further up to cross over before long, and we hope to see more white marble fronts on . . . [this] side of the street,” declared the author of “New York Daguerreotyped” (Putnam’s Monthly) in April 1853. The building—which later housed the New York Sun—still stands at 280 Broadway and is a designated New York City Landmark.

Men, of course, were the primary merchants on Broadway, but women—who shopped not only out of necessity but also as a pastime—were the main clientele. This gender-based activity was sometimes viewed with condescension. “We can hardly wonder that the dear creatures find such enjoyment in ‘shopping,’” sniped the New York Herald on November 16, 1844. “It is her morning visit, her drive, her promenade, her dream at night.” The author derides “the crowd of elegant women, dressed in the first style of fashion, chattering away, and tumbling over the goods, and criticizing each other’s bonnets, and retailing the freshest gossip!” Etiquette doyennes—including Mrs. John Farrar and Eliza Leslie—advised their female readers to treat shopkeepers with courtesy and select purchases carefully. Some disapproving writers, however, even discouraged shopping as a pastime.

Despite the traffic mayhem and a few naysayers, promenading and shopping on Broadway was an experience enjoyed by many, a “scene of gaiety, brilliancy and beauty, and such a mélange of what goes to make up a city,” J. H. Ingraham proclaimed in 1839. “Broadway belongs to his majesty, the people!” he added triumphantly.

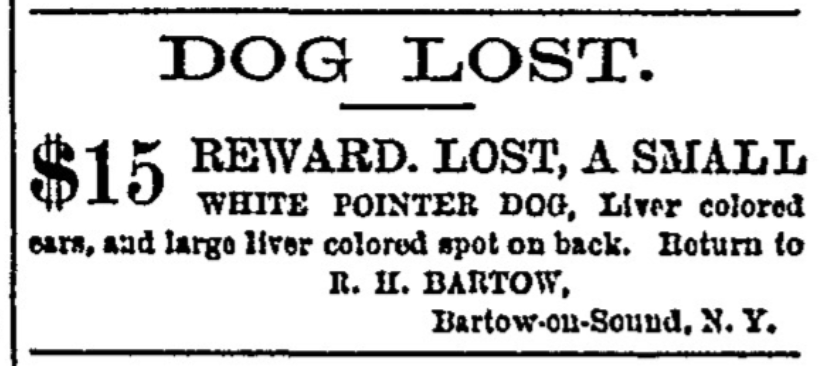

Margaret Adams Highland, Bartow-Pell Historian