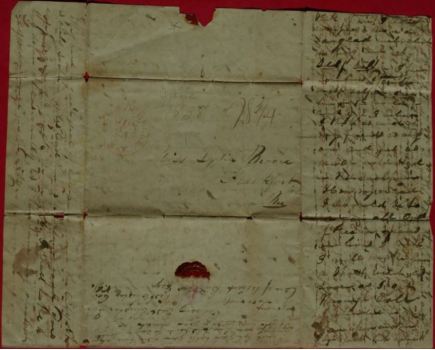

Letter from Augustus Moore to his sister Lydia. In 1838, letters were simply folded, addressed, and sealed. The postage amount was indicated in the top right corner. Stamps were not yet in use.

On June 17, 1838, a young man named Augustus Moore penned a chatty letter full of news from Pelham, New York, to his sister Lydia in Frankfort, Maine, comparing himself to “a roving planet” with “comet-like” movements, “living on hope and moonbeams.” Moore had recently taken a post on the Bartow estate as tutor to two boys in order to “fit them for college”—ten-year-old George Bartow (1828–1875) and his fourteen-year-old cousin Henry Duncan (1823–1904).

“Well I suppose you would like to know what I am doing here,” Moore wrote to his sister on that summer day. In today’s world of instant communication, it is sometimes hard for us to imagine that close family members would not know where we are living, but it wasn’t so simple in 1838, especially for people on the move.

Postage rates at this time were based on the number of sheets of paper and the destination. To save money, correspondents sometimes “crossed” their lines by turning the paper at a right angle and writing over the previously finished page.

Who was this whimsical fellow who worked as a tutor for the Bartow family?

The eldest of five siblings, Augustus Moore was born in Maine around 1810. He attended Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut, and later became an Episcopal priest. For many years, Rev. Moore was the rector at Christ Church in Florence, South Carolina, where he died in 1876. He never married.

Wesleyan University President Dr. Wilbur Fisk

As a college student at Wesleyan, Moore made some important connections. In fact, recent research has revealed that two people mentioned in the tutor’s letter helped him find a teaching position—Wesleyan University President Dr. Wilbur Fisk (1792–1839) and Daniel Whedon (1808–1885), a prominent Wesleyan professor, theologian, and Methodist leader.

Moore tells an amusing story in the letter about his search for employment as a tutor. His mentor Professor Whedon said that a gentleman, whose name he had forgotten, wanted to interview Moore in New York at the Methodist Book Room the following morning at 9 a.m. and had offered to pay his travel expenses from Connecticut. Moore wrote to his sister, “I told my chum I was going to New York—what my business was and he laughed heartily at the idea of me going on such a wild goose hunt—but I got ready as soon as possible, jumped on board the steam boat and off I went.” The tale continues with a few mishaps, but the nameless gentleman turned out to be Mr. Robert Bartow, and Moore “made a bargain to stay with him a year.”

Neptune Island with the steamboat American Eagle after an 1842 lithograph by Currier & Ives (C.H. Augur, New Rochelle Through Seven Generations, 1908)

When the Bartows’ new tutor arrived by steamboat at the Neptune Island landing in New Rochelle, he enthused, “I found Mr. B’s coachman waiting for me with a brougham, which took me to his residence, and when haven’t I been particular enough!” This was an auspicious start to “a prospect of spending the year pleasantly,” with a horse and carriage at his disposal, an abundance of free time, and a kind and sociable family. But true to the young man’s self-described role as a “roving planet,” Moore’s career as a private tutor was not long-lived. By 1844, he had moved to South Carolina where he found his calling in the Episcopal Church.

Margaret Highland, Historian

For more on the tutor’s letter, see 7/26/2011 post “Living in Style: A June Day at the Bartow Estate, 1838”

Pingback: Behind the Closed Door: Privacy by Design in 19th-Century Houses | mansion musings

Pingback: Index | mansion musings

Pingback: The Bartow Children: Life in a Nineteenth-Century American Family | mansion musings