Rose gardens were definitely a thing in the early 20th century. The so-called Queen of Flowers—redolent of summer pleasures—filled gardens large and small with a heady mix of colors, scents, shapes, and sizes that ranged from subtle to dramatic.

The International Garden Club (IGC) was formed in 1914 at a time when many public and private rose gardens were being planted and an interest in gardens and garden clubs was in the air, especially among well-to-do society women. The IGC, an ambitious new horticultural organization, was the brainchild of the energetic socialite and gardener Zelia Hoffman (1867–1929) and her British friend, the author and gardener Alice Martineau (ca. 1865–1956). Mrs. Hoffman recruited a number of wealthy, well-connected garden enthusiasts and horticultural experts as members, and the club leased from the City of New York the old Bartow mansion—located in the Bronx’s Pelham Bay Park—to use as their headquarters. The IGC quickly hired the white-shoe architectural firm of Delano & Aldrich to restore and modernize the dilapidated historic building and to create a formal terraced and walled garden with a fountain. The members raised an extraordinary sum in a very short time—about one hundred thousand dollars—to pay for these projects, which were completed in 1915. The only thing missing was a rose garden . . . but there would soon be a plan for that.

“The number of Rose gardens is nowadays considerable, and they are increasing year by year. . . . At the beginning of the 20th century it is beyond question that every decent estate should, somewhere or other, in a suitable position, include a Rose garden,” declared the great French rosarian Jules Gravereaux (1844–1916) in a 1914 article in the Rose Annual (later reprinted in the 1917 IGC Journal). Rose gardens were sprouting up all over the place.

In early 1916, about five miles from Bartow-Pell, the New York Botanical Garden approved plans for its rose garden—which was designed by the well-known landscape gardener Beatrix Farrand (1872–1959)—and broke ground later that year. The following spring, on April 22, 1917, the New York Times cheerfully announced that the NYBG was planning “one of the great rose gardens of the world.” Farrand’s garden opened in 1918 (but was not completed until 1988). At the same time, on the other side of the Bronx, the race was on at the old Bartow estate to create its own world-class rose garden. As the club’s Journal put it in August 1917, the IGC was determined to be the first to open a “place [in or near New York City] where the rose can be studied and enjoyed by the general public.”

IGC president Zelia Hoffman adored roses and had glorious ones at Armsea Hall, her palatial house on Narragansett Bay. “One of the attractive features of Mrs. Hoffman’s Newport garden is the long rose arbor over a path leading down to the sea,” writes the rose-smitten author of “The Woman and Her Rose Garden,” published in The New Country Life in June 1917. “It is the especial pride of Mrs. Hoffman and demonstrates to what state of perfection the blooms may be brought by one who knows the rose and its needs.”

Meanwhile, another impressive private rose garden could be found about five miles north of the Bartow estate at All View, the famous yachtsman C. Oliver Iselin’s spectacular waterfront mansion at Premium Point in New Rochelle. The garden was published in the Architectural Review in May 1908 and was undoubtedly overseen by Mrs. Iselin, née Hope Goddard, who was an avid gardener (as well as “the only woman ever to sail as a member of the crew defending the America’s Cup,” according to her 1970 obituary in the Times).

Other notable early 20th-century American rose gardens include Elizabeth Park in West Hartford, Connecticut (1904)—which was the first municipal rose garden in the United States—and those of Henry and Arabella Huntington at San Marino, California (1908), the White House (1913), and the E. M. Mills Rose Garden in Syracuse, New York (1924), all of which still flourish today.

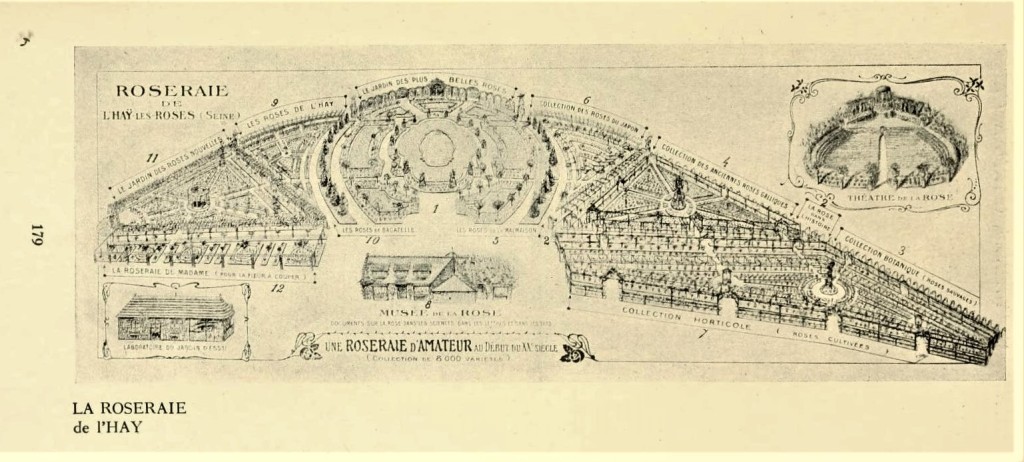

Delano & Aldrich’s proposal for the IGC was inspired by the Roseraie de L’Haÿ (now known as the Roseraie du Val-de-Marne), Jules Gravereaux’s celebrated rose garden at his house near Paris. (Beatrix Farrand also looked to Gravereaux’s garden when she drew up her plans for the NYBG.) Monsieur Gravereaux made his fortune as an executive at the renowned Parisian department store Le Bon Marché. He began collecting roses in 1894, and by 1910 his extensive garden included all the roses known in the world at that time. Furthermore, as an illustrious rosarian and good citizen who enjoyed an exciting project, he advised the city of Paris on the new rose garden at the Château de Bagatelle in the Bois de Boulogne and donated a number of roses for it. In addition, at the Château de Malmaison, where Josephine Bonaparte had had a famous rose garden, Gravereaux re-established many of the empress’s original varieties by studying the botanical illustrations drawn by her court artist Pierre-Joseph Redouté.

In August 1917, in the IGC’s new horticultural journal—Journal of the International Garden Club—William Adams Delano (1874–1960) announced his plans for the club’s magnificent rose garden. The garden must “be accessible for the public, as well as for members.” Good soil, perfect drainage, and a southern exposure were required. “All these conditions were found in the remains of an old apple-orchard near the main entrance to the Club, just East of the entrance drive.” Furthermore, “the old apple-trees, if they can be preserved, will give an air of age to the Garden.” Delano wisely notes: “Every garden to be enjoyed must have a sense of privacy. It will not do to have motor cars whizzing by in full view, nor can the beds dwindle off into daisy fields without well-defined boundaries.”

The IGC’s rose garden would sit on gently sloping ground “only a step from the entrance gate and from the Club House.” It would be divided into terraces and be framed by walls, balustrades, and steps to “pull the whole together,” the architect writes. There would be five collections of roses on three levels. The categories were historical, botanical, “modern” (19th century), “new” (20th century), and “finest blooms,” such as Madame Caroline Testout, Captain Christy, Frau Karl Druschki, Madame Ravary, and La Tosca.

“An arbor covered with a profusion of rambling, climbing roses” would line the perimeter, and “a planting of vines and trees” would grow to stretch “their branches over the wall on the north, east and west,” adding “another charm to the Garden and keep[ing] off the cold winds.” The arbors were designed to connect four classical-style “small houses” with pedimented entrances, which were to stand at the center of each side of the garden walls. One of these edifices was the main entrance, which would “contain a stairway leading to the central terrace.” The other three buildings would house a “collection of pictures of roses,” a card catalogue, and a library, “where all the literature pertaining to roses that can be found will be collected.” A fountain—surrounded by “a collection of the most perfect roses”—would serve as a focal point for the symmetrical design. The idea of a formal rectilinear terraced garden with a central fountain ties the proposed rose garden to Bartow-Pell’s 1915 formal garden, also designed by Delano & Aldrich.

The planting plans reflect Jules Gravereaux’s ideas on a rose garden de collection. The “real Rose garden should not be merely decorative but contain a collection . . . resulting from a deliberate selection,” he writes in “La Roseraie de l’Haÿ” (1914). “The Rosary de collection” he adds, “is the result of an intimate cooperation between the Rose lover and the landscape gardener.” Gravereaux observes, rather disapprovingly, that the decorative rose garden, “which may be termed a garden adorned with Roses, is very much in vogue today.” But, in his opinion, that approach “is like a pretty woman without brains. She may attract attention for a time, but does not retain it.”

The English-born horticulturalist Arthur Herrington (1866–1950)—whose distinguished career included working in Britain for the influential landscape gardener William Robinson—had recently overseen the horticultural work for the 1915 formal garden at Bartow and was to be in charge of “laying out and developing the [rose] garden,” according to the IGC Journal.

The thrilling new garden would be a collaborative project led by Zelia Hoffman (IGC president), William Adams Delano (architect), and Arthur Herrington (landscape gardener). Eighty pages of articles about roses in the 1917 IGC Journal added to the buzz. The club was on a roll. So, why was the proposed garden never built? The answer is World War I.

The war changed everything. “A campaign to raise funds for the building of a Rose Garden, modelled after those near Paris of Bagatelle and the Roseraie de l’Hay, had just been started this spring when we entered the war,” Hoffman reports in the IGC Journal of August 1917. “The site of the Rose Garden will be for the present planted to vegetables. The grounds of the Club will be offered to the Westchester Red Cross Society for open air hospital purposes in case a large number of wounded should come to us.” She has more to say in “Shall We Grow Roses in Wartime?,” in the 1918 American Rose Annual. “I only regret that the great municipal rose-garden which the International Garden Club has projected for the City of New York is not existing and ready to do its share in bringing inspiration, relief, and peace to the wounded among our people in this torn and agitated time,” she laments. The moment had passed, and the IGC’s rose garden was buried in history.

Margaret Highland, Historian

Pingback: Free and Cheap NYC Events, Saturday July 18th, 2020! – Cheap Chick in the City

Pingback: Index | mansion musings