A short path lined with horse chestnuts on the grounds of Bartow-Pell leads to a romantic little woodland cemetery where half a dozen eighteenth-century headstones nestle under towering shade trees. The seventeenth-century Pell manor house, which tradition says was destroyed during the American Revolution, once stood nearby. It is unknown whether or not the burial ground actually contains human remains, and it is possible that some or all of the gravestones were moved here from another location a very long time ago.

Six tombstones dating from 1748 to 1790—including one for Joseph Pell, the Fourth Lord of the Manor of Pelham—surround a memorial tablet added in the nineteenth century. The other stones are for Pell’s widow, Phoebe; their young married daughter Susannah; a toddler son of Phoebe and her third husband, James Bennet(t); Saloma Pell, who was also a toddler; and “Isec” (Isaac) Pell, a teenager. The old cemetery has been an object of historical interest since at least 1848, when Robert Bolton Jr. described it in A History of the County of Westchester. Its location on ancestral land made this a venerated site for the Pell family; they added the large memorial stone in 1862 and a fence with inscribed granite posts in 1891.

Bartow and Pell genealogy is complex. The tapestry of intermarriages and other relationships can make one’s head spin. But the bottom line is that in 1836, when Robert Bartow purchased the property that had once belonged to his grandfather John Bartow (and to his great-great-uncle Joseph Pell), he took possession of an estate with deep connections to both his Bartow and Pell ancestors.

Joseph Pell was thirty-seven when he died in 1752. Probate records indicate that his death took place shortly after that of his father, Thomas Pell II, the Third Lord of the Manor. According to Joseph’s will—written on August 31, 1752, when he was “very sick and weak”—he and his wife “Phebe” had six children (three sons and three daughters), and their education was important to him. His will stipulates: “The income of my estate is to be used for maintaining and bringing up my children to good learning.” His wife and his “loving friend” John Bartow (1715–1802) were among the executors. This particular John Bartow was known within the family as “old Uncle John.” He was an unmarried son of the Reverend John Bartow, who had emigrated from England to New York in 1702.

Phoebe (or “Phebe”) Pell was Joseph Pell’s widow. She died in 1790 “in the 70th year of her age.” At his death in 1752, Joseph left his wife “£400, and a good bed and furniture, and 6 chairs, a looking-glass, a trunk and a table, and the use of all lands until my sons, Joseph and Thomas, are of age.” Records indicate that she married two more times. In 1758, Phoebe Pell wed Boswell Dawson, and in 1762, she married James Bennett. Their son John Bennett died at the age of twenty-one months on August 6, 1765. His headstone is in the Pell plot, as is that of his mother.

The gravestone of Joseph and Phoebe’s daughter Susannah is also in the cemetery. She married Benjamin Drake in 1759 and was the first of his four wives. Susannah was only twenty-two when she died on March 4, 1763, probably from complications following the birth of her second son, Benjamin, on February 21.

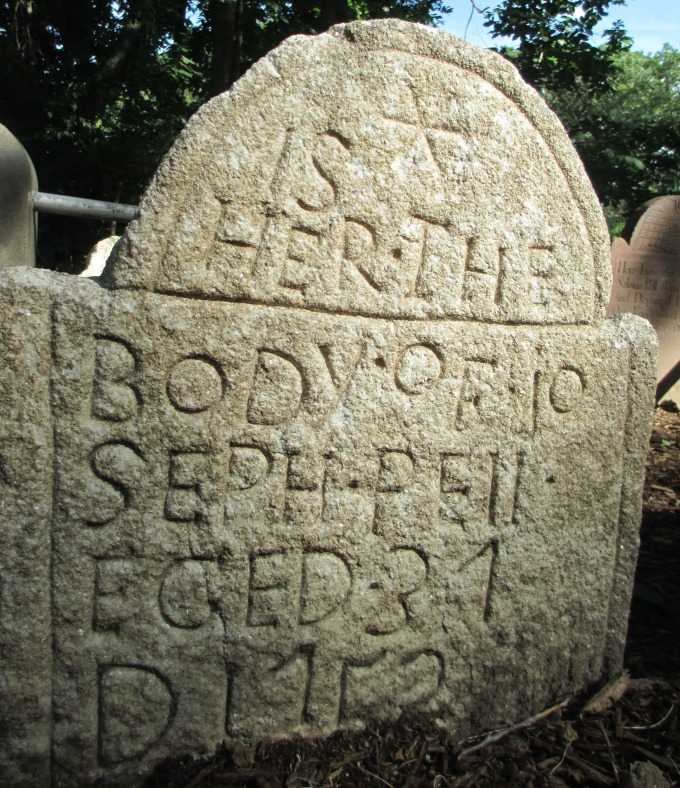

The exact relationship of Saloma Pell and Isaac Pell to the other people in the cemetery is unknown. Saloma died in 1760, a few months before her second birthday. Writing in 1878, Evelyn Bartow described the burial ground and erroneously lists “Salome” as a child of Joseph Pell, but Joseph died seven years before Saloma was born. “Isec” (or Isaac) Pell’s tombstone is the earliest in the plot. The inscription has been variously transcribed, sometimes leading to the interpretation that he died on December 14, 1748. However, a closer reading indicates that Isaac died at the age of fourteen on an unknown date in 1748. Further research will perhaps reveal more about Saloma and Isaac.

People of means, like the Pells, could afford to hire a stonemason to make a tombstone for their loved one. Early Colonial stones often featured memento mori, such as a death’s head, as grim reminders of an uncertain eternity and the Last Judgment. But the Age of Enlightenment and the Great Awakening produced a more benevolent philosophy towards the afterlife. Accordingly, in the mid-eighteenth century, cherub motifs began to appear on headstones as serene and hopeful reminders of heaven.

The Pell cemetery includes stones in several styles. The earliest ones belong to Isaac Pell (1748) and Joseph Pell (1752) and appear to be by the same hand. The crude letterforms are similar, the spelling is poor, and they are made from the same type of fieldstone. Each has a simple pinwheel or star motif at the top. The most elaborate and beautiful marker belongs to Saloma Pell. It has been attributed to the master stonemason John Zuricher, who was active in New York, New Jersey, and elsewhere from the 1740s to the 1770s. Stylistic elements found in Zuricher’s work appear on Saloma’s headstone and include a winged cherub’s head with a square face and low-slung puffy cheeks surmounted by a crown.

As is commonly known, life expectancy in the eighteenth century was a dire prospect. The shadow of death was omnipresent. Disease could carry away several family members in one fell swoop, and many people lost precious young children to scarlet fever and other illnesses. Childbirth was perilous, and postpartum infections could turn deadly, as may have been the case with Susannah Pell Drake. Primitive medical practices sometimes did more harm than good.

When someone died, a family member or friend stayed with the body and kept “watch.” Corpses were dressed in shrouds, and an open coffin allowed people to pay their respects until the funeral took place. (To learn more about shrouds, listen to Colonial Williamsburg’s podcast.) Black mourning clothes were donned by the well-to-do, a custom that had been introduced to Colonial America from Europe. And, like a macabre party favor, funeral goers received mourning gloves and memorial gold rings as a tribute to the dead. According to research published by the New England Historical Society, Andrew Eliot, a minister at Boston’s North Church, amassed 2,940 pairs of funeral gloves over thirty-two years beginning in 1742. (To reduce this stockpile, the enterprising pastor sold many of them.) In addition, friends and family of the deceased enjoyed a large repast and alcoholic beverages as part of the funeral rituals.

Thanks to a 2012 Partners in Preservation grant from the National Trust for Historic Preservation and American Express, Bartow-Pell was able to restore the Pell family burial ground along with the mansion’s terraced garden. The cemetery and its beautiful setting are lovely in all seasons—autumn, winter, spring, and summer—and provide an intriguing glimpse of history in Pelham Bay Park.

Margaret Adams Highland, Bartow-Pell Historian

Pingback: Greek Revival Mystery: Who Designed the Bartow Mansion? | mansion musings

Pingback: Pell Family Burial Ground | New York City Cemetery Project

Pingback: Pell Family Portraits: Amelia Grace Pell Craft and William E. Craft | mansion musings

Pingback: Index | mansion musings