Bartow-Pell’s formal double parlors feature two center tables.

What’s the big deal about center tables, and why does Bartow-Pell have so many of them?

The center table was an essential piece of furniture in American parlors in the middle of the nineteenth century. It was not only useful; it was also imbued with complex social and cultural meanings. As a practical matter, center tables—which were frequently the focal point of parlors—were suitable locations for oil lamps and other lighting devices, which were often placed in the middle of the table in order to distribute precious light evenly, especially during the evening. The table’s round form also allowed people to sit close together and created convenient gathering spots for sewing, reading aloud, conversation, and other group activities. “‘We have been talking about getting a centre-table,’” a young wife reminds her husband in Three Experiments of Living (1837). “‘I thought it would be very convenient; and then it gives a room such a sociable look; besides, as we had a centre-lamp!’” she pleads.

Illustration from American Girl’s Book: Or, Occupation for Play Hours by Eliza Leslie, 1831

A. J. Downing, The Architecture of Country Houses, 1850, fig. 223

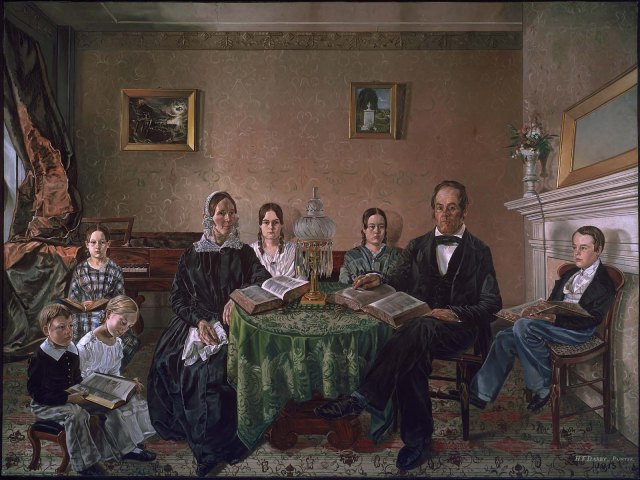

Center tables took on a kind of moral connotation, however, beyond simply serving as a domestic asset. In 1850, Andrew Jackson Downing wrote in The Architecture of Country Houses that they “have long been popular pieces of parlor furniture,” and the “centre-table is to us the emblem of the family circle.” In 1854, a writer in Family Miscellany and Monthly School-Reader advised that the center table helped promote learning as well as good morals:

Let the family be supplied with books and periodicals. When evening comes, wheel the table into the center of the room, bring on the lights and gather around them. While the mother is busily engaged in sewing, and the daughter with knitting, and the younger children in some quiet but innocent game of amusement, let the father or son read from an interesting volume, now and then pausing, that all may join in a brief conversation on the subject. . . .From the associations of such a home, and family-room, and center-table, with its stores of knowledge, there would go forth into the world . . . young men and young women with a social influence which would banish from society much of its selfishness.

Bartow-Pell’s family sitting room. An oversized Bible sits on the center table, which is covered with a period-appropriate green cloth.

Henry F. Darby (American, 1829–1897). The Reverend John Atwood and His Family, 1845. Oil on canvas. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Gift of Maxim Karolik for the M. and M. Karolik Collection of American Paintings, 1815–1865, 62.269 www.mfa.org

Ladies sew and converse around a center table. Fashion plate from Godey’s Lady’s Book, January 1853

Center tables and their affiliation with the parlor, often a feminine domain in nineteenth-century households, prompted Godey’s Lady’s Book to publish a column called “Centre-Table Gossip.” The tables were also bourgeois status symbols. “The Center-Table,” a short story published in 1850 in Gazette of the Union, Golden Rule, and Odd Fellows Family Companion, begins:

“Husband,” said Mrs. N——, “I think we must have a center-table. I have some very tasteful volumes, and some beautiful shells, and a variety of things with which to furnish it; and indeed our parlor is quite singular without it, they are so common now.”

“Well, Mary,” replied her husband, “the house is your own domain, you know. Arrange it to your own taste.”

As these passages show, items found on center tables varied, and they revealed what was important in different households. Books and periodicals could indicate an emphasis on education and learning, or they might have been on view merely to demonstrate good taste. An oversized Bible was often included. “Her centre-table contained a large Bible . . . one or two annuals in gay attire, the daguerreotype of her absent son, and a cologne bottle,” wrote Mrs. J. H. Hanaford, mixing the sacred with the secular in “The Centre-Table versus the Dining-Table,” from The Water-Cure Journal (1853). “Rich confusion” is described in this poem from The Monthly Miscellany of Religion and Letters (1840):

A small round table in the centre placed,

With Bible, hymn book, and the annuals graced;

The daily paper and the last review,

Tracts, pamphlets, billets, old as well as new,

With inkstand, wafers, sand-box, paper, knife,

In rich confusion there.

Sinumbra lamp, French, ca. 1820. Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum, Gift of Stuart and Sue Feld 2014.04a,b

Publishers, manufacturers, and advertisers took advantage of society’s devotion to the center table. For example, in 1852, a book notice in The National Magazine Devoted to Literature, Art, and Religion declared that “exquisitely engraved” Bible illustrations in recently published volumes would “form an elegant addition to the library, or centre-table.” Sewing baskets, books, writing supplies, and the like—which were happily scattered on center tables in back-parlors and sitting rooms—would not usually clutter a formal parlor. Instead, tables in the best rooms of the house might feature a floral arrangement, sinumbra lamp (a “shadowless” lamp with a circular oil font and a glass shade), or decorative object as an elegant centerpiece.

Even though center tables often had marble tops, table cloths were fashionable accessories. According to A. J. Downing: “Centre-tables depend for their good effect mainly on the drapery or cover of handsome cloth or stuff usually spread upon their tops, and concealing all but the lower part of the legs.” And an article in the Merchants’ Magazine and Commercial Review (1859) informs us that “Almost every parlor center-table is covered in winter by a woolen table-cover.” Although a variety of color and fabric options were available, green baize or broadcloth was a common choice.

Table design. Thomas Hope. Plate 39 from Household Furniture and Interior Decoration, London, 1807

American center tables as a furniture form were inspired by French and English sources. The British Regency designer Thomas Hope (1769–1831), for example, published a “round monopodium or table in mahogany” in his book Household Furniture and Interior Decoration (1807), which scholars have linked to American table design. And French-style gueridons, or round tables, with marble tops, were made in early nineteenth-century New York by the influential Parisian émigré cabinetmaker Charles-Honoré Lannuier (1779–1819).

In Bartow-Pell’s formal double parlors, two center tables date from the second quarter of the nineteenth century. Casters allow them to be moved easily, as originally intended, reminding us that the set-up for today’s First Friday concerts is not entirely unlike what the Bartows would have done for their evening parties. Upstairs in the mansion’s family sitting room, a typically large Bible and items for family activities surround an oil lamp on the center table. Yet another table, with a lap desk, inkwell, and books, is located in the seating area of the master bedchamber.

American center table in the Grecian Plain style, ca. 1835–40. Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum. Gift of Mrs. Robert Brace, 1986

Although Bartow-Pell currently has several center tables on view, it is unknown how many the Bartow family actually owned. Curators in historic house museums such as Bartow-Pell that do not retain their original furniture use their best knowledge to interpret period rooms, and they rely on donations, monetary gifts, grants, and loans of objects from collectors and other museums to gather appropriate pieces. Over time, new resources and ongoing scholarship allow collections to be refined.

In modern households, the center table is a thing of the past. Lamps have electrical cords that need to be plugged into outlets, so tables with lamps must be next to a wall. Families often gather in front of a television set instead of reading aloud in a circle. And people don’t need a special place to keep a lap desk since lap-top computers can be used almost anywhere.

Although times have changed and center tables are no longer a household essential, they are still a must-have at Bartow-Pell.

Margaret Highland, Historian

Pingback: Classical Reflections: Recent Gifts from Richard T. Button | mansion musings

Pingback: Beneath the Grime: A Dazzling Center Table Revealed | mansion musings

Pingback: Index | mansion musings