Bartow-Pell’s carriage house in the snow

“Ah! This looks like winter!” Snow started to fall in New York City at around two o’clock in the morning on Wednesday, January 21, 1846. It snowed hard all day, “and it wasn’t any of your common, pin-feather snow but came down in flakes almost as big as bricks,” the New York Herald reported excitedly. The next day dawned clear and bright. The sun shone “down upon the pure snow [and] made the streets and housetops glisten like diamond mines.” Conditions were perfect for “sleighing mania.”

The Sleigh Race, ca. 1848. N. Currier, publisher. Hand-colored lithograph. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Americans in cold climates were crazy about sleigh riding. Sleighs were not only sources of wintertime fun, but they were also used by both individuals and businesses when roads were impassable. Period sources—such as newspaper articles, short stories, songs, diary entries, and engravings—provide endless details about the use of sleighs in the 19th century.

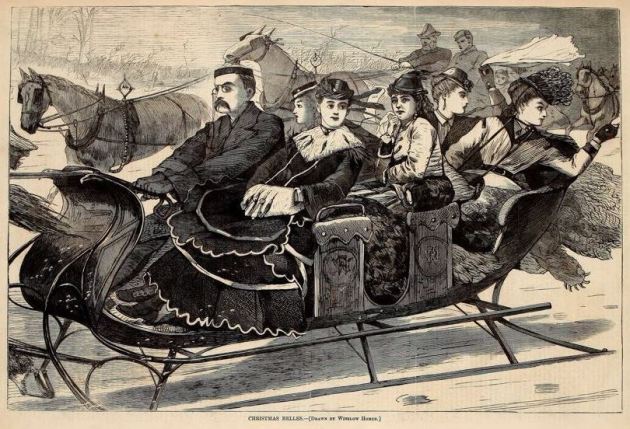

Winslow Homer (1836–1910). Christmas Belles. Wood engraving from Harper’s Weekly, January 2, 1869

Just imagine the exhilaration of the fresh, bracing wind whooshing and blowing in your face as the horse quietly trots along the snowy ground to the sound of jingling sleigh bells. Fleecy rugs, furs, and blankets keep everyone cozy and warm. The winter merrymakers sing songs and wave and halloo to onlookers and passing sleighs.

Thomas Benecke (American, active New York, 1855–56), artist, and Nagel and Lewis, printer. Sleighing in New York, 1855. Color lithograph with hand coloring. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Edward W. C. Arnold Collection of New York Prints, Maps and Pictures, Bequest of Edward W. C. Arnold, 1954. This scene from the 1850s depicts heavy sleigh traffic on Broadway in front of Barnum’s Museum. Stage sleighs, a dandy and his belle, boys with snowballs, and a myriad of other revelers enliven the scene while a brass band serenades them from Barnum’s balcony.

In the city, a good snowfall muffled the usual cacophony of rumbling carriage wheels and the clip-clop of horseshoes on the paving stones. The sleighing season—or New York’s “winter carnival”—was enjoyed by people from many walks of life.

Broadway and other principal streets were filled at an early hour with vehicles on runners of all sorts, sizes, and descriptions. Here comes a splendid sleigh drawn by four black prancing steeds—fine fur robes line it, and protect its inmates from the cold. In it are packed half a dozen persons—the father, the mother, and the children. It is the “above Bleecker” millionaire taking a ride with his family. . . . Then here comes an exquisite with a huge moustache and long curled hair—on his head he wears a peculiar fur cap nearly a foot high, which protects his ears, and his body is encased in a huge fur coat. His sleigh is a curious one, hardly large enough, one would think, to contain a man. The bows are brought together in the form of a serpent’s head. . . . And then comes the mechanic, and the clerk, and the laborer, and all sorts of people in all sorts of sleighs, all laughing and happy. Whoop! Hollo! Here they come—a long splendid sleigh, drawn by sixteen horses, who glide, almost lightning-like with the huge vehicle, over the snow. It is packed closely full of old men—young men—merchants—clerks—tailors—hatters—bakers—milliners—seamstresses—and, in fact, with everybody who could raise a sixpence to take a ride with. This is the truly democratic sleigh. New York Herald, January 26, 1846

Click here to view a short film from the Library of Congress of sleighing in Central Park made in 1904 by Thomas A. Edison, Inc.

American Winter Scene, ca. 1867. Joseph Hoover, publisher. Color lithograph. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Sleighing in the countryside had its own charms, even though it lacked “the excitement of a dashing, sweeping ride on one of the avenues,” as the New York Herald put it. William Augustus Bartow (1794–1869) had a business career with his brothers (including Robert, who built the Bartow mansion) but later became a farmer near East Fishkill, New York, in an area close to the Hudson River where he and his wife raised ten children. Accounts of sleigh riding are scattered throughout the journal he kept from 1837 to 1870 (now in Bartow-Pell’s archives). For example, on December 30, 1855, the family “went to church in [the] sleigh.” The diarist also noted that January 1865 was a very cold month with “sleighing since the 9th,” which continued until March. Sleighs were also kept at the Bartow mansion in Pelham, and a sleigh, sleigh bells, and a wolf skin were listed on the estate inventory of oldest son George L. Bartow (1828–1875), who lived at home with his parents, Robert and Maria, on their country estate.

Sometimes sleighs overturned or collided with each other. On the bright side, red noses and snowball-throwing boys were among the less serious drawbacks of sleigh riding.

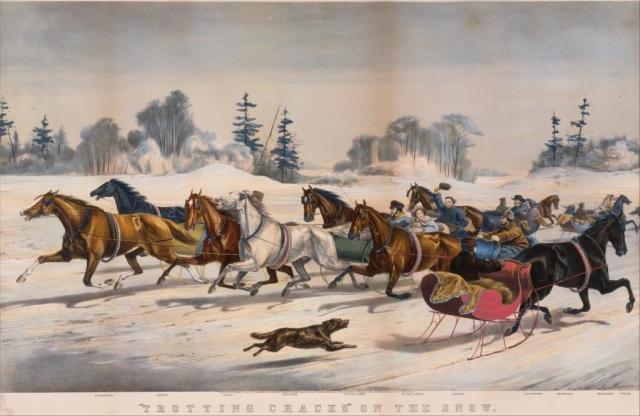

Louis Maurer (1832–1932), artist, and Currier & Ives, publisher. “Trotting Cracks” on the Snow, 1858. Hand-colored lithograph with tint stone. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Bequest of Adele S. Colgate, 1962

Sportsmen and harness racers relished a good heart-stopping sleigh race with their trotters. In his bestselling book, the noted driver and trotter trainer Hiram Woodruff (1817–1867) recalled an electrifying race in the winter of 1842 through the not-yet-developed reaches of upper Manhattan. “The snow flew where it had drifted, and the runners of the sleighs made it shriek again as they slid over it to the music of the bells. I kept ahead, making the pace hot. . . . As we neared the city, the crowds grew greater, there was more noise and cheering, and more furious jangling of the sleigh-bells as the gentlemen drove their horses about. The more the noise and confusion, the greater the speed of Ajax. . . That was sleighing!”

A Moon-Light Sleigh-Ride, no date. Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division

Moonlit sleigh rides were enjoyed by both urban and rural revelers. On January 23, 1846, the New York Herald related that “countless numbers of sleighing parties were out, many to a late hour, many all night. Those of our citizens who slept had a fine opportunity of testing the power of merry music in inducing sleep, for the sleigh bells jingled in the city all night.” In the country, young people enjoyed what was known as a sleighing “frolic,” with supper, a dance, and—needless to say—plenty of flirting.

Sleigh-frolicking ranks very high. In small [American] country towns or villages, parties of a dozen or twenty young people (male and female) embark on board three or four sleighs, cutters, etc., and when the nights are beautifully clear, but cold as severe frost can make them, they will drive ten or fifteen miles into the country to some comfortable little tavern . . . where they spend a few hours in mirth and jollity, regaling themselves with the best that the establishment affords; when, having ate, drank, sung, danced, and “frolicked” until a pretty late hour, the sleighs are once more got ready, and in high glee and spirits they drive merrily home again. Each horse being provided with a string of good bells, the lonely and silent forests are often thus enlivened at the solemn hour of midnight by the jocund tinkling of the rapidly-passing sleigh bells. Many little love affairs are said to originate in these “sleighing-frolicks.” “Sleighs and Sleighing Frolics,” The Penny Magazine, September 9, 1837

Hollywood cameras follow a love-struck couple bundled up on a romantic nighttime sleigh ride in Christmas in Connecticut (1945), a holiday film about a spunky pair played by Barbara Stanwyck and Dennis Morgan. Click here to view a clip.

Sleigh riding also inspired an entire musical genre. Almost everyone loves “Jingle Bells,” the catchy song written in the 1850s by James Lord Pierpont (1822–1893), which was originally entitled “The One Horse Open Sleigh.” But that is just one of dozens of songs and other pieces of music written for or about sleighing, especially in the second half of the 19th century. “Sleigh Ride Galop,” “Sleighing Glee,” “Sleigh Bells,” “Sleigh Bell Polka,” “Pat Fay’s Sleighing Party,” and “Sleighing on a Starry Night” are just a few of the many examples in the Library of Congress. To listen to a 1913 recording of “On a Good Old-Time Sleigh Ride,” click here.

Sleigh riding also inspired an entire musical genre. Almost everyone loves “Jingle Bells,” the catchy song written in the 1850s by James Lord Pierpont (1822–1893), which was originally entitled “The One Horse Open Sleigh.” But that is just one of dozens of songs and other pieces of music written for or about sleighing, especially in the second half of the 19th century. “Sleigh Ride Galop,” “Sleighing Glee,” “Sleigh Bells,” “Sleigh Bell Polka,” “Pat Fay’s Sleighing Party,” and “Sleighing on a Starry Night” are just a few of the many examples in the Library of Congress. To listen to a 1913 recording of “On a Good Old-Time Sleigh Ride,” click here.

Henry Collins Bispham (American 1841–1882). A New York Street Scene—“Pork versus Milk.” Wood engraving from Harper’s Weekly, March 7, 1868.

The New York Coach Maker’s Magazine, November 1858

There were many types of sleighs. Stage sleighs—or omnibus sleighs—could carry large numbers of passengers for a “remarkably low charge.” Mail sleighs, milk sleighs, and coal sleighs ensured delivery of essential items. And 19th-century Americans would have recognized “pung,” “cutter,” and “jumper” as various kinds of sleighs. One of the most popular recreational sleighs was the stylish Albany cutter, a lightweight model with a curvy, almost whimsical design that was known to be favored by Santa Claus and was first made by the well-known carriage and sleigh maker James Goold of Albany, New York. Sleighs were painted in red, black, or other colors and embellished with painted decorations such as stripes. “The cutter and sleigh painting of ’94 will be a fine show of colors. Fashion be praised!,” exulted the writer of “Paint Shop Gossip” in the October 1894 issue of Painting and Decorating.

Cutter, 19th century. Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum, TC1993.04. This is one of two sleighs in Bartow-Pell’s carriage house collection.

Bells with decoration such as this are called “petal” bells. This one is a size 2.

The jubilant tones of sleigh bells make the perfect holiday soundtrack. “Just hear those sleigh bells jingling, ring ting tingling too,” runs the 1948–50 classic song “Sleigh Ride.” More importantly, however, bells were early warning signals of an approaching sleigh as it glided softly—and sometimes noiselessly—over the snow. Starting in 1808, William Barton of East Hampton, Connecticut, popularized a method of making one-piece sleigh bells with the jinglet (pellet) inside during the casting process, and East Hampton foundries became the leading producers of sleigh bells in the 19th century.

Speaking of jingle bells, what could be more exhilarating than the thrill of “dashing through the snow in a one-horse open sleigh” and “laughing all the way?”

Margaret Highland, Historian

Pingback: Just Up the Road: Henry James’s Cousin Minny Temple | mansion musings

Pingback: Index | mansion musings