This is the first in a series of posts about headline news in mid-nineteenth-century New York.

“Time’s up.” “That’ll do.”“Shut up.” “Go to bed.” “Take a drink.” Hissing. Groans. Stamping of feet. Contemptuous laughter. General uproar and confusion. And countless loud interruptions by derisive, raucous men. “Friends, will you keep order!” This is what greeted women (and their male supporters) at the Woman’s Rights Convention in New York City on September 6 and 7, 1853. Because of these unruly and hostile troublemakers, the gathering later became known as the Mob Convention.

The convention took place at the Broadway Tabernacle, a well-known church between today’s Worth Street and Catherine Lane. During the same week, some activists also participated in anti-slavery and temperance meetings at the Metropolitan Hall, a grand, new theater about a mile north on Broadway (which, by the way, burned to the ground a few months later). But reformers were not the only attractions in town. The Exhibition of the Industry of All Nations (America’s version of the 1851 Great Exhibition in London) was drawing crowds uptown at the New York Crystal Palace in what was then known as Reservoir Square (now Bryant Park).

History of Woman Suffrage (edited by Susan B. Anthony, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, and Matilda Joslyn Gage) points out that the crowd of antagonistic men at the 1853 convention openly showed—as never before—the sort of “public sentiment woman was then combating.” The mob, the author adds bleakly, clearly confirmed “that general masculine opinion of woman” which, turned into law, “forges the chains which enslave her.” Things were heating up, and converting the opposition was not going to be easy.

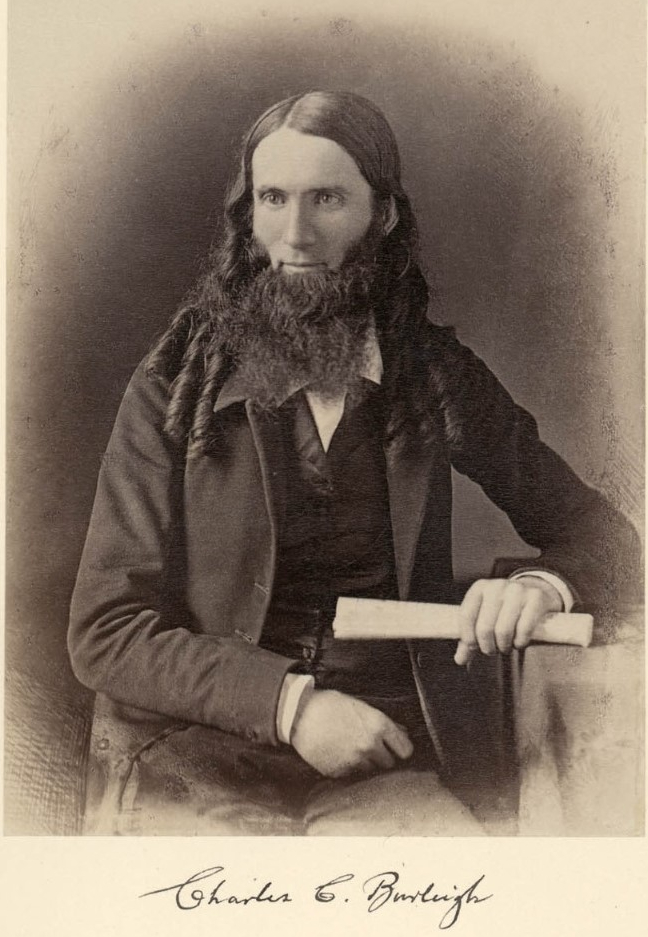

The meeting was chaired by Lucretia Mott (1793–1880), the abolitionist and social reformer who had teamed up with Elizabeth Cady Stanton to organize the groundbreaking Seneca Falls Convention five years earlier in 1848. Other influential reformers—both women and men—took the stage in 1853. Lucy Stone (1818–1893) was a gifted orator and an early female graduate of Oberlin College who kept her maiden name after marriage. The Reverend Antoinette Brown (1825–1921) was the first ordained female minister in the United States and had just been prevented from speaking at the Temperance Convention because she was a woman. Sojourner Truth (1797–1883) gave her moving speech “What Time of Night It Is” amid hisses, rude laughter, and applause. Dr. Harriot K. Hunt (1805–1875) was a physician who specialized in women’s health. Susan B. Anthony (1820–1906) was there, too. The abolitionists William Lloyd Garrison (1805–1879), Wendell Phillips (1811–1884), and Charles C. Burleigh (1810–1878) were among the sympathetic men who participated. A few opponents were also given the chance to speak.

Press coverage was extensive and lasted several days. The New York papers were represented in force at the reporters’ table—including the Tribune, the Herald, and the newly launched Times. Each had its own distinct point of view, ranging from progressive to very conservative (just like the media in today’s democracies). “The Tribune was independent, and fearless in the expression of opinions on unpopular reforms,” a writer in History of Woman Suffrage later recalled. “Its editor, Horace Greeley, ever ready for the consideration of new ideas, was on many points the leader of liberal thought.” The Herald, the author continues, “was recognized by reformers as at the head of the opposition, and its diatribes were considered ‘Satanic.’” Finally, because the Times was “established at a much later date, its influence was not so great or extended as either The Tribune or The Herald.” In the writer’s view, “It represented that large conservative class that fears all change . . . knowing that in all upheavals the wealthy class is the first and greatest loser. From this source the mob spirit draws its inspiration.”

The press gave wildly different attendance figures for the opening session. According to the Times, only about three to four hundred individuals, mostly women, were present. The Tribune, on the other hand, reported that there four to five times that many people in “an audience of about 1,500 persons, composed about equally of men and women.” In any case, increasing numbers of rowdy adversaries crowded the cavernous church on Broadway and often drowned out the speakers on the platform. An inflammatory writer for the Herald even provoked a nineteenth-century flash mob by promising hecklers good entertainment if they would “put a shilling in their pockets [the price of admission] and journey toward the Tabernacle.” By the evening of September 7, the large space overflowed with three thousand people.

It is fascinating to compare contemporary newspaper accounts written from the scene. “The Bloomer Comedy: Second Day’s Proceedings of the Woman’s Rights Convention” was the Herald’s disparaging front-page headline on September 8, 1853. (Some of the women wore shortened skirts with trousers—i.e., bloomers—which became associated with the women’s rights movement in the early 1850s after such outfits were worn by Amelia Bloomer, Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Lucy Stone, and others.) The Herald makes many more sneering comments, such as referring to the meeting as the “Woman’s Wrong Convention.” Unapologetic and blatant sexism abounds in their coverage. “It is almost needless for us to say that these women are entirely devoid of personal attractions. They are generally thin maiden ladies, or women who perhaps have been disappointed in their endeavors to appropriate the breeches and the rights of their unlucky lords.” The article refers to these “unsexed women” and their “champions” as the “Greeley Clique.” Horace Greeley (1811–1872), the founder and editor of the New-York Tribune, was at the convention and joined with a policeman to help quiet a disturbance in the gallery, according to one of his paper’s rivals, the Times (September 7, 1853).

On September 8, Greeley’s paper described the convention’s final proceedings in “Tremendous Uproar: Close of the New York Session,” saying that when the Tabernacle doors were thrown open at about seven o’clock, the “rush for tickets and admissions by the anxious throng could only be equaled to that on a Jenny Lind night.” After a tumultuous evening, the convention ended with “shouting, screaming, laughing, stamping,” and so much noise that nothing could be “heard or done in order.” Although “the Convention broke up amid the wildest uproar,” a resolution was passed giving thanks to Lucretia Mott “for the grace, firmness, ability and courtesy with which she has discharged her important and often arduous duties.” Even the unfriendly Herald grudgingly complimented the women’s “coolness and self-possession,” despite not having “right on their side.”

The belligerent mob could not deter advocates for women’s rights. On the last evening of the convention, Lucy Stone stood up on the platform to thunderous applause from supporters and deafening interruptions from insolent men in the gallery. Although the clamor was so great that her words were barely caught by reporters, she hoped that people “would remember what had been said, and one day there might be a convention when the men of New York would work with women for their rights.” “And then,” she went on, “men won’t believe the scenes that have been enacted here, [and] that men should be found to come here in solid phalanx to gag down women.” After declaring that the women in the room “were not to be frightened by trifles,” Stone announced that another convention would be held a month later in Cleveland, Ohio.

Margaret Adams Highland, Bartow-Pell Historian