This post is gratefully dedicated to Cheryl Hepburn Greenhalgh, the outgoing board president of Bartow-Pell, who has served from 2013 to 2016, and from 2019 to 2024.

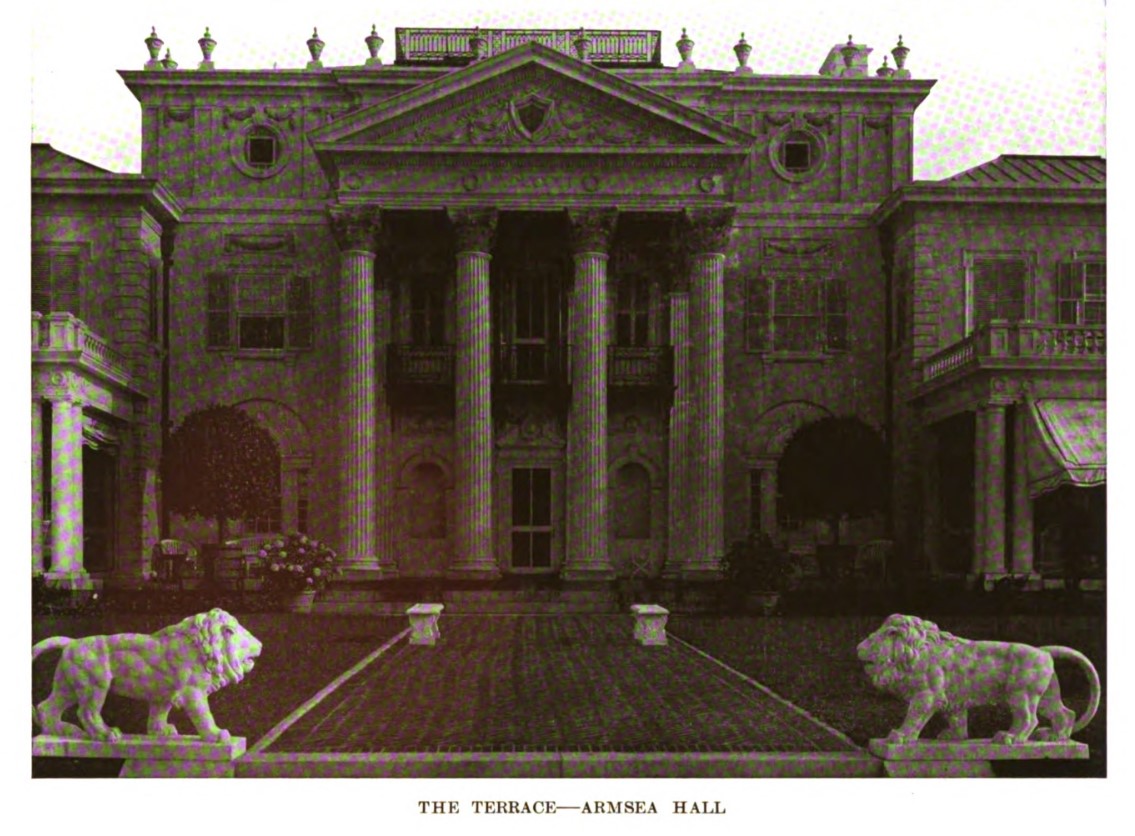

Every year at Armsea Hall, her palatial Newport estate overlooking Narragansett Bay, Zelia Hoffman waited eagerly for the Dorothy Perkins roses to burst into bloom toward the end of July. Luckily for us, the well-known garden photographer Frances Benjamin Johnston immortalized this rambling profusion of colorful pink blooms with her camera on a sunny day in the summer of 1914. In addition, these two women of unlimited energy and vision had a working relationship that went beyond the borders of Zelia’s celebrated rose trellises.

In the early twentieth century, Frances Benjamin Johnston (1864–1952) was a dynamic pioneer in the new field of professional garden photography, which she elevated to the status of fine art. As in landscape painting, she viewed her subjects through the lens of an artist, capturing the personality and mood of her subjects and creating garden portraits through close observation and a sensitivity to light, shadow, composition, and color. Johnston was also a famous promoter of the Garden Movement, spreading the gospel of nature through the publication of her photographs in the popular home and garden magazines of the day and in a series of illustrated lectures across the United States that featured hand-colored lantern slides of her work. “The beauty of nature is a cult to me,” she proclaims in “Your Garden Can Be Beautiful, even if You Raise Cabbages (Telegraph-Courier, Kenosha, Wisconsin, June 2, 1921). “Householders are realizing that beautiful exteriors make for happy homes. The very work of puttering about a garden is wholesome to mind and body.” Johnston’s activities were widely covered by the press, which was also excellent publicity for her photography business.

Johnston moved to Washington, D.C., as a child and grew up in an affluent household. Her father worked for the Treasury Department, and her mother (who was clearly a strong female role model) was a journalist covering national affairs. As a young woman in the 1880s, Johnston spent two years in Paris, where she studied at the Académie Julian, the prestigious art school attended by the American painters Cecilia Beaux and John Singer Sargent. (She later used this early artistic training to develop her painterly approach to garden photography.) In 1888, the inventor and entrepreneur George Eastman, a family friend, gave Johnston a Kodak camera, and in the early 1890s, she started to hone her skills as a visual storyteller through work as a photojournalist.

“By rare artistic ability, a brilliant intellect, perseverance and energy, she has now won for herself an almost national reputation,” The Photographic Times declared in November 1895. By this time, Johnston’s father had built a studio for his daughter in the backyard of their Washington home, and her highly successful business now included requests for portraits from a number of A-list sitters, such as first lady Frances Cleveland. But new horizons beckoned. White-shoe architectural firms and their fashionable clients were keen to offer commissions for exceptional photographs of various building projects, residences, and estates, and splashy new house and garden magazines needed good illustrations. Furthermore, by the 1890s, publishers were finally able to reproduce photographs—thanks to modern printing methods—instead of relying on engravings and lithographs as they had in the past. Johnston, who had already published photographs of the White House, moved into a new phase of her career as a photographer of the country estates and gardens of the wealthy American elite. In 1909, she won a contract from the Beaux Arts architectural firm Carrère & Hastings to photograph the recently completed New Theater in New York City. The glamorous metropolis was also the perfect place to pursue new clients. (Zelia Hoffman, for instance, later hired Johnston, and perhaps it was no coincidence that Carrère & Hastings had designed the Hoffmans’ townhouse at 620 Fifth Avenue.) Johnston took advantage of these opportunities and moved to New York City with the recently divorced photographer Mattie Edwards Hewitt (1869–1956), her business and romantic partner.

Frances Benjamin Johnston was a self-proclaimed New Woman, an iconic symbol of the Progressive Era. As an independent thinker and a champion of social reform and women’s rights, the bloomer-wearing, bicycle-riding New Woman shook things up in the mid-1890s. Johnston was in stride with the zeitgeist when, in 1896, she staged a photo of herself in this modern role, smoking a cigarette, holding a beer stein, wearing a working-man’s cap, and crossing her legs like a man.

Johnston and Hewitt were applauded in the press as trailblazing professional women. “Here is how two women in New York have created a distinct photographic field for themselves by a combination of technical expertness and artistic appreciation, taking commercial photography out of humdrum lines and stamping it with personality and distinction,” Eva vom Baur wrote in Wilson’s Photographic Magazine in June 1913. These intrepid—and at times, daring—women were known to push boundaries to capture the right shots. They blocked traffic and clambered onto window ledges and housetops. “To get the Masonic Temple at Twenty-Third Street and Sixth Avenue, we were obliged to climb to the top of the chimney of a nearby building,” Johnston calmly told Vanity Fair in December 1912 in “They Photograph the Smart Set.” On August 8, 1915, Johnston and Hewitt were highlighted in “The Best Paid Occupations for Women” in Washington’s Evening Star, and the following month Johnston was one of fifty professional women who participated in a lecture series at New York University on how and why women succeed in business. Johnston and Hewitt worked together in New York from 1909 to 1917, but after a falling out, they continued their long careers separately.

Zelia Krumbhaar Preston Hoffman (1867–1929), also known as Mrs. Charles Frederick Hoffman Jr., was a wealthy horticultural enthusiast, philanthropist, and clubwoman who moved in the highest circles of New York society. In addition to managing her Newport estate and her Fifth Avenue townhouse, she was an energetic leader with big ideas and a long list of accomplishments. The year 1914 was a busy one for Zelia, mostly because she founded not one, but two garden clubs. One of these was the International Garden Club (IGC) in New York City’s Pelham Bay Park in the Bronx, whose well-heeled members (many of whom lived in Manhattan) hired the architectural firm of Delano & Aldrich to restore the old Bartow mansion for use as the club’s headquarters (now Bartow-Pell Mansion Museum and Gardens). The IGC also created an array of gardens, published a journal, formed a library, and organized lectures and flower shows, all within a few years. The idea of such a club had been suggested to Mrs. Hoffman by her friend Alice Vaughan-Williams Martineau (ca. 1865–1956), a British garden writer and designer (whose home near Ascot was photographed by Johnston in 1925). In 1914, Zelia Hoffman also helped found the Newport Garden Club and served as its president. After her husband’s death in 1919, she moved to England, and in the early 1920s until her death in 1929, she leased Blickling Hall, a grand Jacobean mansion and country estate in Norfolk that is now part of the National Trust. Mrs. Hoffman also stood for Parliament as the Liberal candidate for North Norfolk (and lost). (To learn more about Zelia Hoffman, click here.)

Zelia Hoffman and Frances Benjamin Johnston were part of the great age of the American garden. From backyard gardeners to horticulturalists, from society matrons to schoolchildren, gardening was a cultural trend that literally blossomed across the United States in the early twentieth century. It was during this time, for example, that a number of garden clubs were formed, including the Garden Club of America in 1913. Women of the Progressive Era were quick to pull out their gardening tools to create a beautiful environment. “This tremendous interest in gardening has been brought about mainly through woman’s effort, for women now-a-days tuck up their skirts, put gloves on their hands, and dig and plant and prune and water until they make a barren spot into a paradise of beauty. Every garden means a home,” The Touchstone magazine explained in December 1917 in “Garden Photography as a Fine Art.” Even women who employed their own private gardeners were known to get their hands dirty, “digging and planting, clad in knickerbockers and rough jackets, or in smocked frocks, designed to make women look as artistically beautiful as their surrounding flowers,” we learn in “Women Are Gardeners on Own Estates,” published on May 10, 1914, in the New York Tribune. Although gardens had become increasingly important as status symbols for the rich, these showplaces also provided inspiration for others.

Zelia was occupied in helping to establish the Newport Garden Club—which was incorporated on August 4, 1914—when Frances Benjamin Johnston and Mattie Edwards Hewitt were behind the camera in the Hoffmans’ rose garden. According to Sam Watters in Gardens for a Beautiful America: 1895–1935, Photographs by Frances Benjamin Johnston, Johnston and Hewitt went to Newport in 1914 at the behest of Mrs. Hoffman, taking photographs not only of Zelia’s roses, but also of the gardens of her friends in the Newport Garden Club. According to Watters, Zelia Hoffman “was the first to publish photographs by Johnston-Hewitt in a garden club journal, the 1915 Annuaire of the Garden Club of Newport.” A short time later, in September 1915, Zelia—switching over to her role as president of the International Garden Club—commissioned Johnston and Hewitt to photograph Delano & Aldrich’s newly completed formal garden at the IGC clubhouse in the Bronx. These images were published in the club’s inaugural Journal in August 1917, and Johnston made some of them into lantern slides for her lectures. Zelia Hoffman had something else in common with Johnston and Hewitt—the women were neighbors on Fifth Avenue near 50th Street (where Rockefeller Center stands today). Zelia and Charles F. Hoffman’s townhouse was at 620 Fifth Avenue, and Johnston and Hewitt had a studio for a few years at 628 Fifth Avenue. It was, indeed, a small world.

In their own separate ways, Zelia Hoffman, garden club president, and Frances Benjamin Johnston, groundbreaking photographer, were passionate advocates for the Garden Movement and emblematic women of the Progressive Era. Today, the Frances Benjamin Johnston Collection at the Library of Congress provides public access to the photographer’s extraordinary body of work, comprising about 20,000 photographic prints and 3,700 glass and film negatives, some of which are available to view online. As for Zelia, her legacy lives on in the beautiful house and gardens at Bartow-Pell.

Margaret Adams Highland, Bartow-Pell Historian